Spoilers for the finale of My Next Life as a Villainess

My Next Life as a Villainess: All Routes Lead to Doom! has quickly become renowned as something of a bisexual power fantasy. Its protagonist, Catarina Claes, is transported to a fantasy world in which she finds herself at the centre of a multi-gender love triangle—or perhaps love octagon is the better term—and the series treats this perfectly matter-of-factly.

Never does the narrative, or any of the characters, bat an eye at the fact that girls and boys fall for Catarina (and that, even if she can’t quite put a name to her feelings, Catarina herself seems equally flustered by attention from both). In fact, the way characters interact, background details, and the general framing of the narrative all add up to make the world of Villainess itself seem oddly, and refreshingly, queer-friendly.

In speculative fiction, there is still an ongoing convention that fantasy worlds that take inspiration and aesthetics from history must include real-world prejudices or erase certain groups entirely in the name of a certain vision of “historical accuracy.” The truth is, fantasy world-building is a chance for writers to play with convention and provide escape from those prejudices, and imagine a world of their own making where they do not exist. At a glance, the setting of Villainess could be such a place.

Beyond Catarina’s romance options, there are some elements that suggest this world as a sort of magical anyplace where queer identity is accepted and queer relationships are allowed to flourish. There are, however, also a few gaps where the series falls short on this, or at least leaves the viewer with unanswered questions. So, is the world of Villainess a queer utopia uniquely laid out so that Catarina’s love(s) can bloom? Or is the question of world- and story-building a little more complicated?

Villainess is an isekai with a slightly different take on the power fantasy tropes usually embedded in the genre. Catarina, the daughter of a noble family in a magical world, bumps her head one day and is flooded with the memories of her past life as a geeky Japanese high schooler. She is rocked by the realization that she’s been reborn into the world of Fortune Lover, the last visual novel she was playing before her death—and further shocked by the realization that she has been reborn not as the protagonist but as the game’s snooty villainess, who was fated to die or be cast out in exile at the conclusion of the game.

Using her memories of Fortune Lover’s characters and plotlines, Catarina hatches a plan to avoid her doom. She befriends as many characters as she can, rewrites tragic backstories, and, most importantly, is kind and supportive to the game’s heroine, Maria, rather than being her enemy.

Catarina’s mission is to survive the game’s story, but an unintended consequence of her working so hard to not play the villain is that she becomes the heroine herself. Now, instead of falling in love with Maria, all of the game’s main characters, including Maria and the other women, have all fallen for Catarina.

This kind of mixed-gender harem is a refreshing rarity, especially given how frank Villainess is about it. Mary and Sophia are treated as love interests just as much—in fact, at times more so—than the boys are, and the first season ends with Maria unambiguously declaring that she wants to be with Catarina. All the while, the show has a running gag (you could even say it is the series’ central premise) where Catarina is too oblivious to realise that her seven closest friends are in love with her. So it remains to be seen who, if anyone, she will resolve this romantic tension with. Nonetheless, Catarina became something of a “disaster bi” icon as the series was airing.

As well as the presence of an unambiguous multi-gender love-octagon, I was impressed by how casually queer Villainess was overall. Sophia, Mary, and Maria are never shown fretting over their crushes on Catarina and their feelings are never derided by other characters. There is some headbutting among the more jealous members of the group of love interests, but none of it seems to stem from homophobia or any notion that girls “shouldn’t” love other girls.

In fact, the only “but we’re both girls!” logic comes from Catarina herself. When Maria confesses her love to Catarina at the end of the series, Catarina’s response is to be baffled, because in the game Maria usually delivers that line of dialogue to her chosen (male) love interest. “So why is she saying it to me?!” her internal dialogue asks. This is Catarina’s textbook obliviousness, of course, but it’s interesting to note that the only character who doesn’t take same-gender romance for granted is the one from the “real” world.

The question arises: is Fortune Lover’s fantasy kingdom a paradise free from heteronormative assumptions? From Catarina’s memories of the original otome game, it does not appear so. Fortune Lover seems fairly straightforward and heteronormative, starring a female main character with four (five, if you count the secret route) male love interests to pursue, each embodying a familiar romance trope like the playboy with a heart of gold or the charming but manipulative prince. The only developed relationship Maria seems to have with another female character is with Catarina, who is pitted against her as her rival.

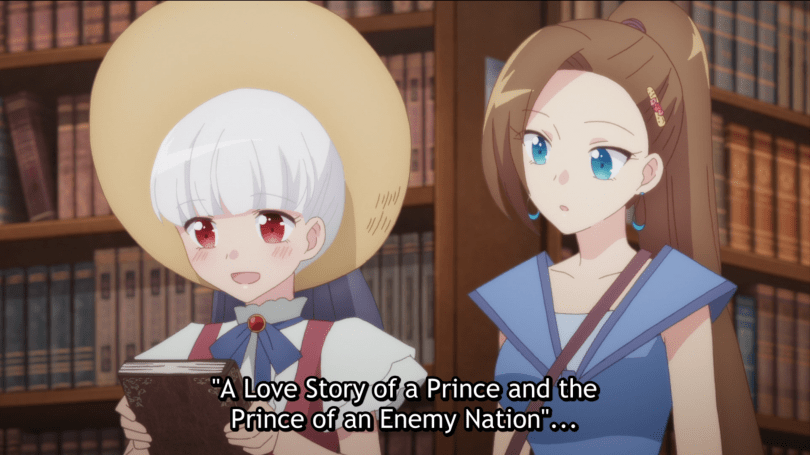

But the world that our protagonist inhabits when reincarnated as Catarina tells a different story, or at least reveals different details. The first thing that stands out are the presence of seemingly mainstream queer romances in the literature of the fantasy world. Catarina swoons over a love story about two young women and that book becomes a way for Catarina and Sophia to bond. Later on, Sophia excitedly references a series about a romance between two princes from rival kingdoms.

Queer representation in fiction is a big part of normalising queerness in society at large, and the increasing visibility of it generally speaks to increasing acceptance. If prince/prince romances are front and centre on their bookstore shelves and storybooks about girls falling in love are easily accessible to younger readers, can we then assume that this fantasy world is accepting of queer love and queer identity? It’s a small detail, perhaps, but this kind of casual mention goes a long way to building the world and implying its attitudes.

In terms of real-life relationships within Villainess’ setting, it seems there is still a convention—at least among the nobility—of heterosexual marriage, with many members of the main cast betrothed to one another. This is nobility in a setting inspired by nineteenth-century Europe, however, so it’s easy to extrapolate that these have been organized for political or financial convenience, and for the security of the bloodline.

In terms of real-life relationships within Villainess’ setting, it seems there is still a convention—at least among the nobility—of heterosexual marriage, with many members of the main cast betrothed to one another. This is nobility in a setting inspired by nineteenth-century Europe, however, so it’s easy to extrapolate that these have been organized for political or financial convenience, and for the security of the bloodline.

Mary mentions running away with Catarina so that they can get married, but it’s not stated whether this is because of heteronormative marriage laws of their home country, or simply the two girls’ respective engagements. There are some murmurings from Catarina’s parents about how her behavior makes her unsuitable to be a prince’s consort, but if any of the other noble parents have society-influenced qualms about their daughters falling for Catarina, the audience is not privy to them. Maria’s mother (who is not a member of the nobility) even seems quite taken with Catarina, and pleased that someone is making Maria so happy.

Of course, while the girls in the cast have crushes on Catarina and no authority figures are actively homophobic, the fact remains that we see no queer couples in Fortune Lovers’ world. Whether it be at the school, a high society gathering, or in and around towns, it would have been an extra validating detail to confirm the queer-friendliness of the setting—even if it was as little as a same-gender pair of background characters holding hands, or calling each other by romantic pet names.

As it is, we’re left in a sort of limbo where queer fiction and queer crushes are seemingly taken for granted, but it remains uncertain if these feelings can be pursued into reality and into adult life.

Perhaps it’s a stretch to suggest that Villainess is set in some sort of queer utopia or is intended as a queer fantasy. Mary’s possessive envy over Catarina falls into some unfortunate “comedic” tropes about predatory, obsessed lesbians. The running gag about Catarina’s obliviousness to her many admirer’s feelings could be a sort of plausible deniability from the series, a device to keep the status quo in place and never commit to a mutual queer romance. Catarina declaring “It’s the friendship ending!” after a girl confesses love to her may seem like a cop-out to some viewers.

If a protagonist is in the middle of a gloriously bi love-polygon, but the narrative never lets her acknowledge this, can we consider it queer representation? Or is asking that question and expecting a straightforward “yes” or “no” answer thinking about things too narrowly?

Perhaps Villainess is not a perfect example of queer world-building, but it would be remiss of me not to acknowledge how refreshing it is regardless. Seeing characters openly gush over queer romance novels and openly discuss their queer crushes, and seeing a group of people sigh together over their shared love for one person (honestly, it feels like the only thing stopping this from legitimately resolving with polyamory is Catarina’s unawareness), feels escapist.

The lack of comment on the romance(s) from authority figures may leave frustrating unanswered questions, but it also leaves gaps and silences that the viewer can fill in with their own interpretations. It also leaves the uncertainty of Catarina’s romantic future entirely down to character-based conflict, rather than any external, social force that would try to keep her apart from her admirers. That in itself is refreshing.

Villainess is not about the hardships of being queer. It’s about navigating a video game and trying not to die, and accidentally collecting four would-be-boyfriends and three would-be-girlfriends along the way! It’s a profoundly silly and fun show that lets queerness exist without comment, and that is valuable in and of itself.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.