Content Warning: transphobia, queerphobia, gender essentialism

Spoilers for all of Fruits Basket

Fruits Basket is one of my favorite anime of all time. I adore its exploration of how people who’ve suffered incredible trauma can put themselves back together. I adore its portrayal of the radical healing power of kindness as an active choice in a world full of misery. I adore how it showcases the complexities of love and how it can be your greatest salvation if you work to nurture and cultivate it. This show makes me laugh, it makes me cry, but more than anything, it makes me hope. It makes me hope that no matter how bad things get, there will always be a second chance waiting just around the corner. Even two decades after the original manga began publishing, it shines just as brightly.

But I’m not here to talk about how much I love Fruits Basket. Today, I’m here to explore one of its most under-discussed problems: its portrayal of queerness.

There are many characters in Fruits Basket who we can read as falling under the LGBTQ+ umbrella. Unconventional gender expression and same-gender attraction are actually quite common among the show’s core cast. However, by the end of the series, most of these characters have given up that part of their identity. One by one as the characters grow up into adulthood, these wonderful acts of queer expression are left behind in favor of fitting into the cishet norm. In this way, the show reinforces the idea that queerness is a transient part of youth, something that people must inevitably grow out of.

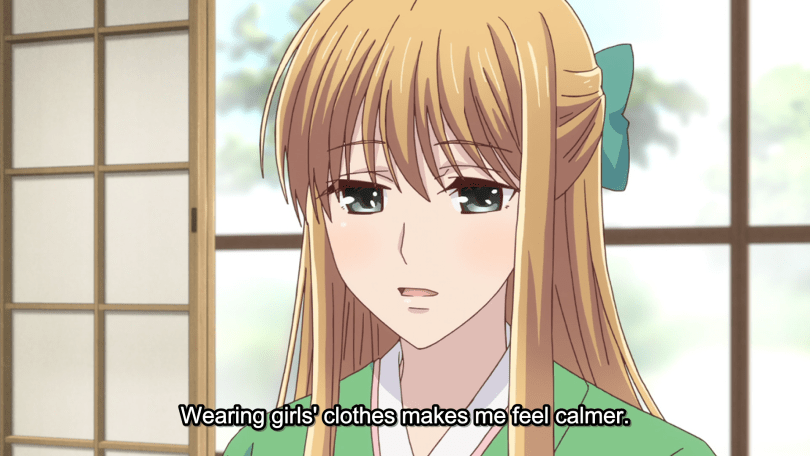

This idea is most explicit with Momiji, the adorable half-German moppet who enjoys wearing a girls’ uniform to school. While Momiji never overtly voices feeling like a girl, it’s clear he enjoys this kind of cross-dressing, and he’s fully comfortable abandoning the masculine presentation expected of him. Sadly, what could have been a lovely example of non-normative gender expression is instead framed by the other characters as something he will eventually have to give up. Sure, he can dress up in girls’ clothes for now, the show says, but only as long as he remains a child.

In this way, Momiji wearing girls’ clothes is framed not as an intrinsic part of his identity or self-expression, but as a childish phase he will eventually grow out of. And sure enough, by the end of the show, Momiji has abandoned his feminine presentation and now wears the standard boy’s uniform.

This running theme is further reinforced with Ritsu, a character who is almost written as a trans woman. While Momiji merely wears a girls’ uniform for the fun of it, Ritsu dresses up as a woman because it makes them feel comfortable and helps them manage their extreme social anxiety. They describe feeling more at peace when they wear women’s clothing, feeling more comfortable in their own skin. I’m not fully transfemme myself, but speaking from my limited experience and the experience of my trans friends, Ritsu’s relationship with their feminine presentation reads so strongly as trans that I’m shocked it wasn’t Ritsu’s intended character arc.

And yet, according to the text of the show, Ritsu is not trans. They are only ever referred to as a cross-dressing man. And by the time the show’s over and Ritsu’s overcome the trauma of Akito’s abuse, they, like Momiji, have returned to dressing solely in “masculine” attire.

There is also the case of Akito, the villain of Fruits Basket. Akito is a woman who was raised as a man to fit her family’s conservative hierarchy and presents herself as such throughout the majority of the show, with short-cropped hair and gender-neutral attire. After her redemption near the end of the series, however, she starts growing out her hair and wearing more feminine clothes.

Not only does this fit the pattern that Momiji and Ritsu have established, it comes with the additional, ugly subtext of an evil “masculine” woman returning to her “proper” feminine presentation once she becomes a good person. Akito’s gender ambiguity is subtextually tied to her role as the Sohma’s abusive tyrant, just as Ritsu’s cross-dressing is subtextually tied to her social anxiety. And once both of these characters grow out of their harmful tendencies, they subtextually grow out of their gender flexibility as well, returning to nice, stable cisnormativity.

So Fruits Basket is poor at handling trans and gender non-conforming characters. But what about gay, lesbian or bi characters? Is there any space allowed for them? Well… kind of. But first, we need to talk about Arisa and Saki.

This one really hurts, because Arisa and Saki are my favorite characters in the show. Their friendship with Tohru is wonderful; I love how steadfastly they support her through her troubles and how much fun they have messing with everyone else. Both of them also have extremely queer-coded backstory episodes describing how they met Tohru in the first place.

To make a long story short, Arisa was a troubled gang member who was saved by Tohru’s kindness and devoted herself to being someone Tohru could be proud to stand beside. Saki was shunned and hated for her psychic powers until Tohru appeared in her life and offered her compassion. Both of these flashbacks are dripping with sapphic energy, including an explicit “I love you” from Tohru to Saki. And even in the present day, Arisa and Saki often drop the L word right back at Tohru. Their relationship feels like it was yanked straight out of a yuri manga at times, with how close they are and how they talk about each other.

Of course, I knew this wouldn’t last, and I was fully prepared for the inevitable “just friends” framing the show decided to go with. Credit where it’s due, in a world that often positions romance as the highest form of love, letting Tohru and her friends share a platonic love that’s just as important as any of their romantic partners certainly isn’t without merit. Still, considering Fruits Basket has no wlw or mlm relationships at all, it can’t help but feel disappointing for this to come so close to portraying explicit queerness without ever truly crossing the line.

But to add insult to injury, not only do Arisa and Saki get paired off with guys, they both get paired off with adult men: Arisa with Sohma Kureno, and Saki with Kyo’s master. The implied queerness of their relationship with Tohru and each other is left behind in favor of child/adult “romance.” I would call it the single most infuriating aspect of Fruits Basket, except it’s not even the worst example of romanticized grooming in the story. But that’s a rant for another day.

And then there’s Hatsuharu, who makes this entire discussion more complicated by being explicitly, unambiguously bisexual. As a child, he had a crush on Yuki, and he still shamelessly flirts with Yuki now that they’re both older. He is clearly unashamed of having romantic feelings towards another boy, and the show never paints those feelings as wrong or unnatural. He is, however, also currently dating Rin, a girl, who remains his only true romantic prospect in the present.

I want to tread carefully here, because there’s an unfortunate tendency in some corners of the internet to consider bisexual people “less valid” if they’re currently dating someone of a different gender. So let me be clear: Hatsuharu having Rin as his endgame romantic partner does not invalidate his bisexuality. He is just as much a bisexual man no matter who he’s currently dating. And the same could arguably be said about Arisa; there’s a moment where she compares her feelings toward Tohru to her romantic affections for Kureno. Small comfort, perhaps, considering the grossness of Kureno being an adult, but still.

So in a vacuum (and absent the predatory age gap, in Arisa’s case), Hatsuharu and Arisu having crushes on same-gender peers before eventually falling in love with someone of a different gender is perfectly fine. It’s only in the context of the rest of the show where they end up feeling like yet more examples of queerness being treated as temporary. Like, I know bisexuality exists and is valid no matter whether you’re dating someone of the same gender or a different gender, but does Fruits Basket know that? Or does it see Hatsuharu and Arisu as simply dallying with childish fantasies before moving on to more “proper” adult relationships? Considering its treatment of GNC identities, the evidence isn’t exactly promising.

Perhaps if there were some actual queer adults in Fruits Basket’s world, it would make those implications seem less intentional. Sadly, no such adults are to be found. The most we get is Shigure and Ayame acting flamboyantly gay towards each other to annoy Hayate, and both of them eventually end up with female partners as well. So queerness in Fruits Basket only exists in children and teenagers, or developmentally stunted people like Ritsu and Akito, who will eventually outgrow it and move on to nice, acceptable cisheterosexuality as fully developed adults.

It’s a shame, because a modern remake could have been a perfect opportunity to create a more queer-friendly version of Fruits Basket, updating and playing with the themes, plots, and character dynamics introduced in the 1990s. This series is about a magical family that transforms when hugged by someone of “the opposite sex,” but what would that mean for the queer members of that family? Would a gay Sohma feel relief at not being blocked from expressing physical affection toward their lover? Could a trans Sohma realize they were trans when they hug someone of the “opposite” sex and not transform? Is the curse queerphobic in nature, or does it respect LGBTQ+ identities? How could that be used to comment on the complexities of sex and gender and the differences between them? There are so many ways to use this series’ central gimmick to play around with queerness, and yet the story doesn’t even seem to realize they exist.

But even if this remake wasn’t willing to make quite such a radical change, there are plenty of ways it could have embraced the queer nuggets already present in the text. It could’ve let Momiji keep wearing girls’ uniforms as he grew up. It could’ve made Ritsu an explicit trans woman. It could’ve reduced the uncomfortable subtext around Akito’s femme transformation. It could’ve fully embraced Arisa and Saki’s queerness and let them remain in love with each other even after Tohru and Kyo start dating. With even just a couple changes, the 2019 Fruits Basket anime could have made queerness a valuable part of its identity, turning it into a real, tangible force in its world instead of just something to be left behind as you grow up. And it’s a shame it didn’t take that opportunity when it could.

But you know what? If there’s one thing that Fruits Basket has taught me, it’s that the truest form of love is one that doesn’t ignore the flaws you wish you could blind your eyes to. Love is not love if it doesn’t see the bad in you as well as the good, if it’s not pushing you to be the best version of yourself that you can possibly be. And if I criticize Fruits Basket’s failings, it’s only because I love it enough to afford it that respect. I only wish, as a queer person myself, that it was able to love me back.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.