Content Warning: Gore/body horror.

Among the diverse genres and demographic categories of manga, seinen is one of the most fascinating. Seinen refers to manga that is marketed primarily to adult men from their early 20s to their 50s; while it is more of a demographic designator than anything else, it serves our purpose as a good umbrella term under which certain types of manga fall. Seinen manga can vary wildly in genre, from horror to historical to romance, and is distinguished from shounen, manga aimed at a younger male audience, mainly by which magazine it is published in.

While it is an extremely broad category, seinen manga generally feature more mature themes and complicated narratives than their more youth-oriented counterparts, and are often violent, gory, and bleak, as in popular examples Berserk and Tokyo Ghoul. With this understanding, a reader wouldn’t be faulted for assuming the same about the works of mangaka Hayashida Q – a cursory glance through her oeuvre of work reveals a gratuitous amount of gore and violence, dark and unsettling narrative threads, and plenty of grotesque imagery. However, when one looks deeper, her seinen manga prove to be so much more.

Hayashida may not be the only female seinen mangaka – there’s Mori Kaoru and Urushibara Yuki, authors of A Bride’s Story and Mushishi respectively, to name just a couple – but she is certainly unique among them. While female-written seinen manga spans a wide array of genres from historical dramas to cooking comedies, Hayashida stands apart from the rest due to her focus on gruesome body horror and gleefully graphic violence. Nevertheless, despite the gore and violence, her work remains distinct from similar manga due to the genuine charm and whimsy that permeates throughout, from her earliest debut short to her most well-known published series Dorohedoro.

Hayashida Q developed an interest in drawing manga at a young age, and by high school she had already decided that she would pursue manga professionally after attending university. She enrolled at the Tokyo National University of Fine Art & Music, and from there her path to becoming a mangaka was clear. According to an interview with SigIkki, an imprint of Viz Media that focuses on manga published by the now-defunct IKKI magazine, she came in second in a manga contest, after which an editor started her down the road to creating manga professionally.

The SigIkki interview continues, with Hayashida briefly discussing her creative process. While she denies having a specific process or any distinctive or particular tools that she uses, she does outline her general creative approach. She describes how she first brainstorms with her editor over the general flow of the story and follows that with rough sketches and designs in a sketchbook. Along with the sketches, she writes up the narrative scenarios using only character dialogue, which she then transcribes to storyboards that will later become the rough drafts of the final manuscript.

When asked about her creative process for designing the covers for the individual volumes, she explains how she uses a variety of materials – including spray paint, cloth, and even the cardboard from Amazon boxes – to create an eclectic collage of found materials which she combines with traditional illustration. From this interview, it is apparent how her varied artistic methods contribute to what makes her work distinctive, and how in this way she has developed a style entirely her own.

Right off the bat, her messy and chaotic artwork is not only incredibly distinctive, but also almost instantly recognizable. Even her debut work – a strange one-shot called Sofa-chan about humanoid spirits that live in furniture – has a certain frenzied energy to the line work and a characteristic absurdity to the story. These qualities eventually became indicative of her particular style, carrying through her work to this day.

The one-shot HUVAHH, written over a decade after Sofa-chan, shows an eclectic absurdity of both visual and narrative elements that nevertheless come together in a strangely perfect harmony. The language of HUVAHH is literally gibberish; it is written in a nonsense language that leaves the reader to rely entirely on the visuals to understand the story. Thus, Hayashida tells her story through visual patterns, repetitive imagery, and characters’ gestures and facial expressions.

While her artwork is hectic and busy, it is also highly detailed and each frame serves a purpose that adds to the overall narrative. This reliance on the frenetic visuals distills the surreal and the eccentric down to their purest forms, creating a wholly unique reader experience. The messy art and convoluted narrative style isn’t for everyone, but the grotesque, chaotic, often undecipherable qualities are exactly what attracts fans to Q Hayashida.

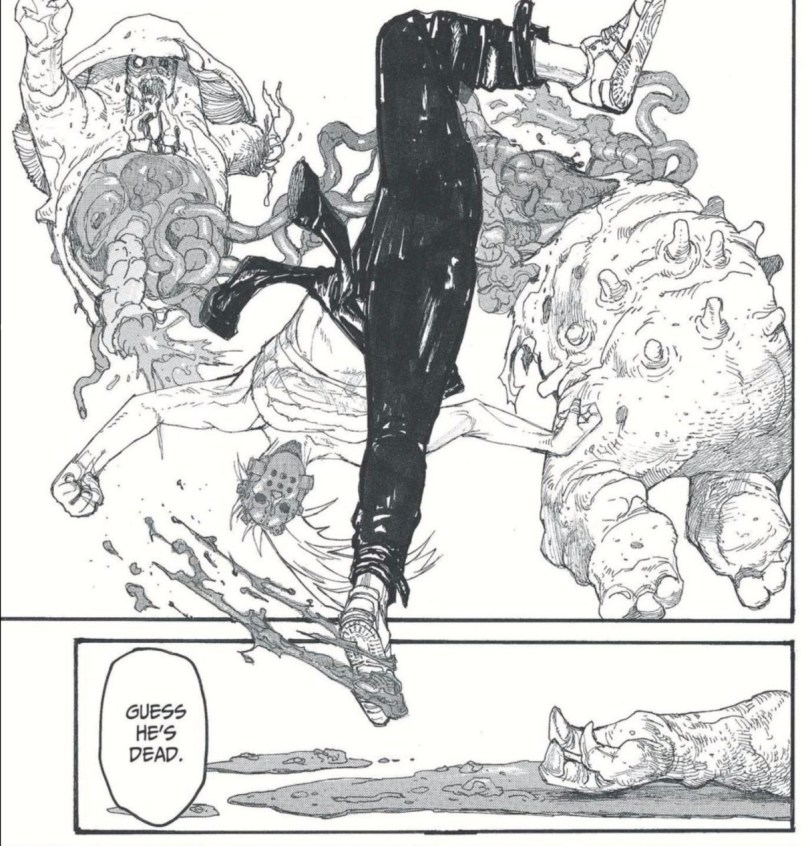

Hayashida’s method of using contrasting elements of horror and comedy set her work apart from other similarly violent and gory manga. While her best known series, Dorohedoro, and her most recent ongoing series, Dai Dark,, are horror manga, they are also comedies. This is especially true of Dai Dark, which follows a young man named Zaha Sanko and his sentient backpack-cum-reluctant guardian Avakian as they traipse through space avoiding aliens who wish to do them harm. Dai Dark is often violent and gory, with a healthy dose of body horror and grotesque imagery, but the antics of the characters and the overall story is more often light-hearted than it is nightmarish.

While Dai Dark arguably falls within the horror genre due to its visuals alone, it remains unabashedly cheerful, quirky, and upbeat. It is a testament to Hayashida’s ability to craft unique worlds that balance unsettling visuals with such a charmingly fun story. And it is precisely this dichotomy between the horrific and the humorous that gives her manga such kinetic energy. Few series can balance such distinct opposites as carnage and whimsy, while still maintaining a distinctly light-hearted tone.

Hanshin Hangi, is a good example that is decidedly less intense than her other works while still being characteristic of her style. The story is relatively mundane, concerned mostly with the daily life antics of an obsessive Hanshin Tiger baseball fan (the dialogue suggests that this is a stand-in for Hayashida herself); and yet despite this relatively ordinary premise, the visuals remain surreal and strange. The unnamed protagonist wears a mask (in this case, a fabric sack with black eye holes to see out of) and the backgrounds are messy, cluttered, and chaotic – all common elements found across her series. While this one-shot may not be nearly as gory as her other works, it is no less absurd or unconventional.

Dorohedoro is Hayashida’s longest-running series to date – running from 1999 to 2014 – and it is also her most well-known and most polished, bringing together all the elements that make up her distinctive visual and narrative style. It tells the story of the amnesiac Caiman, whose head was transformed into a lizard by unknown malevolent magic. He enlists his closest friend Nikaido, a local gyoza shop owner with a murky past, to recover his memories and his original self. Hayashida crafts two worlds that coexist side by side – one of magic users and one of non-magic users – with intricate systems for how the separate societies operate.

Like Dai Dark, Dorohedoro is also a fun, quirky romp despite the grim setting, and not nearly as pessimistic or bleak as the artwork may initially suggest. While her narratives benefit from their comedic tone and world-building, where Hayashida’s work truly shines is the characters, especially in Dorohedoro and Dai Dark. Everyone, from the main characters to the supposed villains to even minor characters, is uniquely designed and charming in their own way. Their relationships and dialogue shine with chemistry and wit, with real affection between them.

The emphasis on friendship would be somewhat strange in any other violent series but makes perfect sense here because of the attention and detail she instills into each character’s unique characterization and personality. While her manga are unquestionably grotesque and disturbing, they are also genuinely heartwarming.

Hayashida’s approach to female characters especially sets her work apart among violent seinen series. Many similar series rely on fanservice to garner attention and popularity, or to showcase their female characters as eye-candy to serve the male gaze. In contrast, Q Hayashida’s female characters are fierce, muscular, and often considerably stronger than their male counterparts, such as the spirit-hungry apparition of death (aptly named Shimada Death) in Dai Dark. They are also loyal, kind-hearted, and selfless.

This is especially true of the women in Dorohedoro, but comes through in her other series as well. While many seinen series use graphic depictions of sexual violence for a quick and easy emotional response, without furthering the development of the victims exploring the deeper themes within, Hayashida chooses to eschew such tropes completely. She also avoids using sexual assault for shock, titillation, or both. Hayashida writes women as fully fleshed out and complex individuals with varying backgrounds, motivations, and goals. Even when depicted nude, they are confident in their nudity and never awkward or ashamed. It’s framed naturally, rather than merely there for titillation or to appeal to the male gaze.

While countless seinen series from countless manga artists represent every genre imaginable, Q Hayashida’s work stands apart. Her manga one-shots and series are often simultaneously serious and goofy, nightmarish and mundane, and it’s exactly that contrast that makes her work so refreshing. It is undeniable that the characters she creates are charming and lovable, the world-building fascinating and detailed, and her narratives compelling, even if occasionally hard to follow. It’s safe to say that I’m excited to see what she’ll do next.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.