Dating sims are one of my guiltiest pleasures. Not the nuanced, introspective ones that ask the players to open up their hearts to emotional vulnerability, but the ones with pastel pink menus and super hunky dudes that are walking, talking stereotypes. I enjoy them for the burst of serotonin I get when my two-dimensional love interest throws a cheesy one-liner my way, but also because I get the satisfaction of seeing the haughty, so-called “popular” girl antagonists get cut down to size.

In the past few years, however, the villainess has seen something of a renaissance. Rather than being the subject of ridicule or comeuppance, she’s being celebrated, given the opportunity to come into her own as the subject of an emerging theme in an ever-expanding field of light novels, manga, and anime. Today I’d like to talk a little bit about these ojous: who they are, where they come from, and why in the 21st century their success demonstrates an alternate world where being smart, hard-working, and kind gets you far.

Otoge, or otome games, are the female-centric half of the dating sim formula. You jump into the story as a newcomer, an ingenue, fumbling your way through the world in order to date and have a happy ending with one or all of the available young men. You’re met with relationship drama, misunderstandings, and opposition from one or multiple other girls.

While there are derivatives, adjustments, and subversions to this basic formula, for the most part each game proceeds in the same way, including their own “villainess.” This girl is typically designed and characterized in such a way that the player is happy to see them punished for their wrongdoings. They’re two-dimensional bullies, vapid and spoiled, without redeeming qualities. At least, from the outside.

The advent of the modern isekai genre—particularly the “reborn in a video game world” variety— brought with it a wave of escapist fantasies. In these isekai, anybody can live out a life of fantasy and power, so long as by “anybody” you mean “any man.” However, from this trend came a new wave of isekai, one that celebrates female protagonists and female-centric stories. It is here that the rise of our villainesses truly begins.

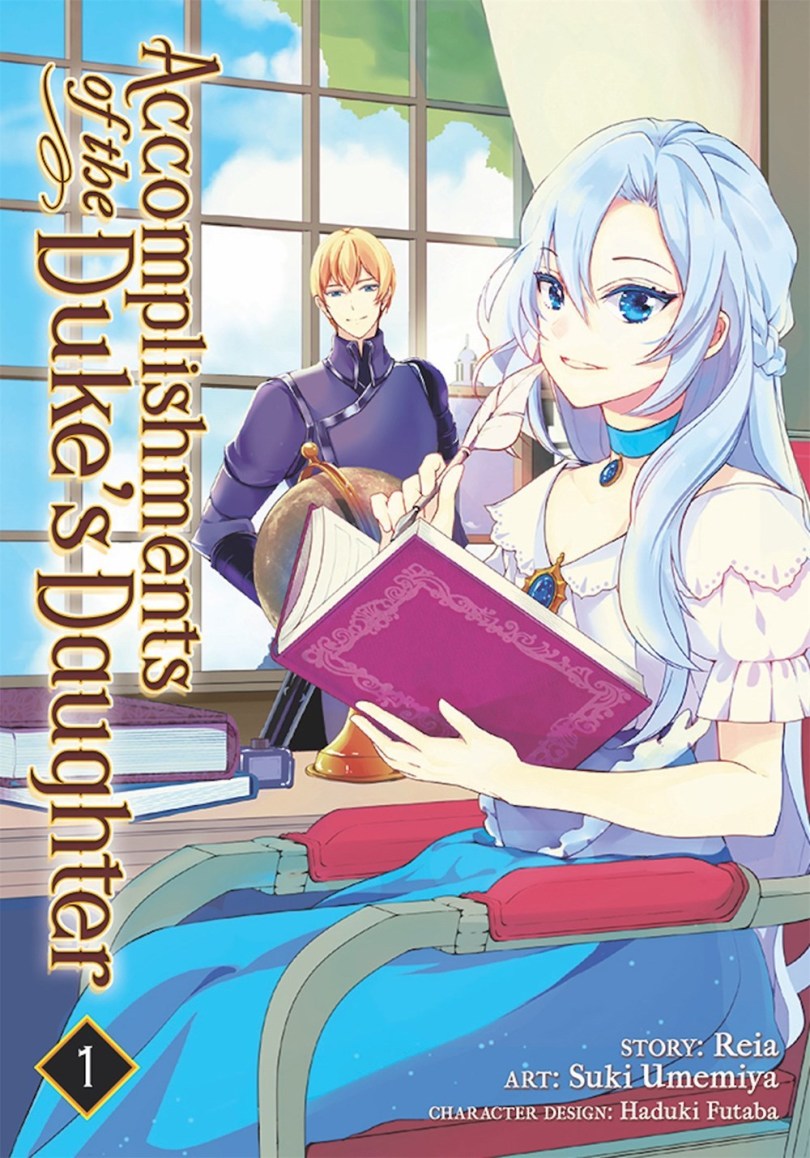

One of the first, and most notable, examples of the villainess reincarnation story is 2015’s Accomplishments of the Duke’s Daughter. Iris, a young woman who played otome games during her life on Earth, now finds herself on the back foot, reborn in the body of the story’s villainess at the exact moment she is being denounced by her former betrothed. From here, she must create a life for herself, serving as the acting lord of her family’s fiefdom.

What made Duke’s Daughter stand out initially was that, in a field of reincarnation stories defined by the characters being reborn with monumental powers or divine blessings, Iris was distinguished by relying on her wits, charisma, and accounting acumen. True, she is born with the advantage of wealth and the natural connections a woman from nobility would possess, but a loss of reputation would normally be an unthinkable deficit for a woman of any noble standing.

Even so, what impressed me throughout every chapter was how well present-time Iris carried herself, as well as what the Iris outside of the main story must have been like. Even before reincarnation, the “villainess” Iris was someone whose honesty and kindness somehow inspired loyalty in her retinue. The version of her shown in the game’s narrative was only a snapshot of a full character.

On the other hand, we have the explosive My Life As A Villainess: All Routes Lead To Doom. Where Iris is composed, intelligent, and accomplished, the newly reincarnated Catarina Claes is… not. She is cheerful, bumbling, and lacks the wits, intelligence, and specialised financial capabilities integral to Iris’ success. What Catarina does have is a working knowledge of the game she’s in, a tendency towards honesty, and an unintentional charisma that draws every single “capture target,” including the heroine herself, into her entourage.

It is almost completely different from the Catarina Claes she should have been. Flashbacks to the game show someone whose haughtiness and bratty attitude drove away anyone who could have ever helped her. Instead, her natural charm and genuine likeability shift this new Catarina into the role of heroine. It gets the reader rooting for her, when they would normally be primed to loathe this character and eagerly await her downfall.

Although quite different in execution and influence, what is clear is that both protagonists succeed by virtue of breaking out of the established villainess roles. In a traditional otome game setting, the villainess exists not even as a foil to the main character, but as a stepping stone for her success.

Within the parameters set by the dating sim genre, the focus and development lies with the male love interests, and the villainess has no room to shine or grow as a character. She is forced by the circumstances of the game and its regal fantasy setting to be part of a patriarchal society, forced to be a lesser person whose ultimate aim is love and romance and the ruin of her fellow young women. Now, however, her fate is allowed to change. She can be more than what she was written to be.

In both My Life as a Villainess and Duke’s Daughter, this is specifically highlighted in the ways that each treats their games’ respective heroines. Iris elects to avoid her predetermined rival Yuri where she can, focusing on uplifting her people and businesses in a way that is specifically highlighted as defying the gender and societal norms of the Kingdom of Tasmeria. It is Yuri who seeks Iris out, goading and almost flaunting her relationship with the main male protagonist while trying to retain a mask of kindness. In this case it is almost as if their roles have been reversed, with Yuri’s behaviour mimicking the bullying and pettiness that Iris was initially accused of.

Catarina, on the other hand, ultimately befriends and unknowingly romances her own heroine Maria. Without meaning to, they form a strong bond, with Maria seeing Catarina as a friend and even companion in the same way almost everyone else in Catarina’s life does.

There’s a refreshing aspect to their relationship, and the conflicts that do arise in My Life As A Villainess come not from a clash in wills or combat over one of the game’s capture targets, but precisely because Catarina is such an important person to those who love her. This unfortunately gets her embroiled in their struggles and difficulties as she rises to their defence, demonstrating qualities more associated with the average heroine such as honesty, openness, and an innate ability to easily make friends.

However, the key similarity is that both of their lives no longer revolve around competition with the “other woman.” The fulfillment each woman finds in her respective life is derived from centering their lives around what actually makes them happy—financial and political prowess for Iris and friendship and dreams of escape for Catarina—rather than the man who is supposed to make them happy.

It flies in defiance not only of the otome genre, but the stereotypical shoujo standard that typically upholds a woman’s standard as defined by her relationship to main male characters. This type of goal-oriented vision is typical of villainess isekai, with works such as Deathbound Duke’s Daughter and The Weakest Manga Villainess also showcasing protagonists seeking a world outside of the path their respective games and manga have set them on.

The power of villainess stories like Duke’s Daughter and My Next Life as a Villainess is that they completely reject the norms of both their settings and the requirements of these games. These are young women whose desire for love is an incidental part of their journey, not a fundamental one. Where male power fantasies most often have their heroes breaking out of the ordinary to be extraordinary and have unique existences, the villainess isekai presents an alternative.

The escapist fantasy for the women in these stories is to break through the confines of arranged marriage and duty, to be recognized for personal merit. To be heroines, yes, but heroines who succeed not because of any magic or swordsmanship but because they are intelligent and empathetic. Not heroes or villains or mob characters, but nuanced people in their own right who are allowed to simply be.

The villainess story could be said to be an evolving genre unto itself, with series like I’m in Love with the Villainess and A Lily Blooms in Another World following in the footsteps of these titles. They create an extensive catalog that showcases villainesses attempting to defy death, trying to live slow lives, embracing their villainous mantles and failing miserably, and now even being romantically pursued by the very girls they should be fighting with.

While not overtaking the vast number of male power fantasies (yet), their presence cannot be ignored. These are characters and authors who refuse to be sidelined or pigeonholed in the archetypal roles set out for women. They demonstrate villainesses who are heroines, heroines who are villainesses, and characters who run every shade of noble and good to morally grey. Their worlds are ones where if you work hard, work smart, and support one another it is possible to affect great change.

True, the “reincarnated villainess defying her fate” tale is becoming surprisingly common, but there’s nothing wrong with that. The world needs fewer tragedies and more happy endings, after all.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.