It didn’t matter if the work was difficult or stressful, or if she hardly earned enough to live on. She didn’t care if she had to live her days as a geek girl or female otaku, with no semblance of a “real” life.

She was never going to stand by and let anyone make fun of her job.

Anime Supremacy!, written by Mizuki Tsujimura and translated by Deborah Boliver Boehm, tells the interconnected stories of three women—a producer, a director, and an animator—working in the anime industry. Not quite a novel and not quite a short story collection, the book is divided into three main chapters, each following one of the protagonists through part of a single anime season.

First, Producer Kayako Arishina achieves her dream of working with auteur director Chiharu Oji—only to have him vanish three episodes into production. Next, Director Hitomi Saito struggles through the mid-episode grind of her first original series as she learns how to balance creative vision with practical needs. And finally, up-and-coming genga animator Kazuna Namisawa ends the season by helping a local tourism board plan on-location “pilgrimage” events for a series her company worked on.

The shifts in perspective each chapter come across as a bit disjointed at first, but the many threads eventually weave together to form a satisfying overarching story. It’s also a thematically fitting narrative structure, given the collaborative nature of anime itself and the novel’s overall focus on teamwork and cooperation. If you’re struggling with the format at first, I encourage you to keep at it, because this really is a story where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

While Anime Supremacy is clearly written with a great deal of love and respect for its characters and the work they do, it’s unlike a lot of “fiction about anime” that gets translated into English because it doesn’t seem to be directly targeting an “otaku” audience. Each chapter opens with its protagonist getting asked the same question, “Why did you get into the anime business?” and there’s a sense that Tsujimura wants to explain that “why” to her readers as much as her characters want to explain it to each other.

This is ultimately a positive, I think, as it keeps the book from feeling too self-congratulatory or insular. But it also leads to a first chapter that’s heavy on detailed industry explanations, oftentimes distracting from the actual (very enjoyable) story. Those curious to know “how the sausage gets made” will likely find these passages fascinating, but for those who either already know or aren’t particularly interested, it can make the early pages a bit of a slog.

That said, veteran anime fans will find their own particular joys in Anime Supremacy, especially in the form of some of its characters and studios. Tsujimura’s impressive Acknowledgments page thanks directors Kunihiko Ikuhara and Rie Matsumoto, animator Hitomi Hasegawa, and representatives from Toei Animation and Production I.G., among others. Knowing that, it’s all but impossible not to see the eccentric “genius” Director Oji as an Ikuhara stand-in and the young visionary Director Saito as Matsumoto—to say nothing of the fictional “Tokei” Animation, where both characters (and real-life inspirations) got their starts.

True to his reputation, Oji was the genius type and was also willful and selfish—that was one nuance of the nickname “The Little Prince.” He suffered excessively over the artistic aspects of a project and thought nothing of dragging other people into his fraught, frenetic orbit.

…Nevertheless, [Kayako had] been enjoying herself immensely. She felt that Oji’s attitude of “wanting to make something really great” was the real thing, pure and unadulterated. To that end, she was willing to humor him all the way.

As a result of all this early exposition, and despite some fantastic comedic beats and fist-pumping moments, the novel takes some time to really get going. Happily, once Anime Supremacy has introduced its readers to the industry, it settles into a sequence of compelling character-driven narratives starring talented, flawed, and dedicated female protagonists.

While each navigates a professional world dominated by men, there are other capable female characters in the story as well, including a few young voice actresses, a famous toy sculptor, and a restaurateur. Each woman is unique in her history, goals, strengths, and concerns, although some of these qualities take time to manifest for the reader.

Tsujimura writes in a close third-person narrative for each chapter and enjoys playing with perspective, meaning that we get to see our protagonists as well as multiple supporting characters from different points of view. As a result, characters who may seem petty or shallow in one scene become loyal friends or respected colleagues in another.

This is particularly true of the other female characters. Our protagonists often fall into the trap of initially viewing other women as “The Competition,” only to have the narrative challenge and eventually reject that mentality, encouraging mutual admiration and support (along with a bit of friendly rivalry, as studios and creative teams vie for the season’s top spot). No character is perfect (and some can be downright maddening), and each person’s goals can vary wildly, but there’s a quiet insistence that the passion and talent everyone brings to the project is valid and worthy of respect.

Some of the supporting VAs gave the impression that it was nothing more than a job to them, but the five stars’ passion seemed genuine—whether they were acting their parts well or poorly or somewhere in between. Their raw will and determination to value their gig and turn it into an accomplishment came through in their heated performances.

That shared passion is essential to the novel’s central ideas and relationships. Throughout these three stories, there’s a strong focus on conflicts between opposing forces or goals as well as the importance of collaboration and compromise (“creative vision” versus “profit” is a common element, but there’s also a tension between “otaku” and “realies” that’s quite deftly handled). Partnerships are key, whether it’s the producer/director working relationships between Kayako/Oji and Yukishiro/Hitomi, or the tourism event-planning between animator Kazuna and civil servant Munemori.

Noticeably, these central partnerships feature a man and a woman, but the novel does a smart job of making them all complex, nuanced relationships, and works in several female friendships as well. Only one of the stories contains a romance, and even then it’s a sub-plot, woven into the main narrative without overshadowing it. Anime Supremacy is happy to talk about the importance of life outside of work and the value of developing relationships beyond professional ones, but those goals always exist side-by-side with its protagonists’ creative endeavors.

Don’t let that fool you into thinking Anime Supremacy is all sunshine and rainbows, though. While the story builds to a triumphant (and unexpected) finale, it isn’t afraid to depict the lower points of being a woman in the anime industry either. In addition to the gender-neutral problems like low pay and grueling hours, casual sexism is sprinkled throughout the story.

Sometimes it’s a major conflict like a male coworker snapping at his superior for “leading him on” because she’s nice to him at the office, but it’s often more subtle prejudices, like an interviewer expressing surprise that “young boys aren’t the only ones who want to ride in a robot.” These moments are often presented with little comment from our protagonists, and while that may be off-putting to some readers, to me it gives the story a layer of reality that’s frequently missing from anime or manga about women in the workplace.

In between kicking ass at their jobs, Kayako, Hitomi, and Kazuna feel insecure about their appearance, worry about their lack (or surplus) of “femininity,” or bristle when someone reminds them that they’re unmarried. Those concerns make them more than just impossible superwomen; they make them real people, working through the same day-to-day bullshit as many women do, and all the more admirable because of it.

On the other hand, Kayako had been shocked by some of the things she’d seen at recent auditions for female voice actors. Perhaps they were trying to appeal to the sensibilities of male directors and producers, but the actress’ costumes ran the gamut from startlingly short miniskirts that showcased their shapely legs, to outfits resembling school uniforms, to designer frocks jauntily accessorized with cat-ear heads. […] After a while, she figured it out. ‘Of course,’ she thought. ‘The actresses dress that way because it gets results.’ And after that she felt a wee bit disappointed in her male colleagues.

Our protagonists aren’t perfect, either. As mentioned before, they fight with internalized sexism and the urge to see more stylish women as “vapid” or “the competition.” They get annoyed or upset at the gendered expectations placed upon them by their coworkers and society at-large. Sometimes they succumb to exhaustion or frustration. In one perfect passage, Kayako calmly decides that she’s going to duck into a bathroom and “cry her eyes out for exactly two minutes” before going back to work.

While a part of me wishes Anime Supremacy had more explicitly called out the sexism baked into many of its characters’ mindsets, the fact that the story shines a light on and challenges them at all is still encouraging. And, by supporting all of its female characters in their various professional endeavors, the novel firmly argues that they do have a place in this world, and a valuable one, despite what some of their coworkers might think.

Where Anime Supremacy is less successful is its overall approach to the anime industry. There are several paragraphs devoted to discussing the low pay or long hours (characters regularly pass out at their desks), but nothing really comes of it. If anything, because the novel is so focused on showcasing its characters’ dedication, it ends up implying (I suspect unintentionally) that the poor working conditions don’t matter because “it’s worth it.” While many within the anime industry likely do feel this way, they should still be treated better, and it’s a shame Anime Supremacy didn’t touch on that more aggressively.

I’m somewhat forgiving of Tsujimura on this point, though, because she’s clearly so much more interested in personal perspectives than she is broader business practices. Her novel is built around the question “why do you work in anime, given what a difficult job it is?”—and the answer, time and again, through sexist coworkers and marketing demands and hellish schedules, is love. These three women and the many people around them love anime because, at some point in the past, they all discovered stories that resonated with them—that gave them hope or an escape or a new way of seeing their world—and now they want to be a part of the process that shares those stories with others.

Hitomi had learned early on, during her own childhood, that life didn’t suddenly turn around and do what you wanted it to do. It was probably no different for kids today. …On the other hand, she didn’t intend to leave children feeling that it was a cruel and heartless story. She wanted to convey the positive, hopeful message that efforts have their proper rewards.

This doesn’t make it okay to exploit workers, of course. But when writing characters who are frequently confronted by outsiders dismissive of their work, I can also understand the difficulty of trying to criticize an industry without disparaging the people within that industry. Ultimately, Tsujimura chose to focus on applauding individuals rather than taking a hard look at the structures around them. This is perhaps a flawed approach, but I can still appreciate a novel that so consistently and ferociously demands respect for its hardworking female leads.

Anime Supremacy may not be crying out for a revolution, but it makes a strong argument for why the people who love and work within a medium that’s so often derided are worthy of admiration (and by extension, one would think, of fair pay and reasonable hours). It lauds their passion and commitment and encourages its readers to not only find something they love, but to also appreciate the work that other people love as well, even if it’s different from their own.

Despite a slow start, Anime Supremacy builds to a narratively sophisticated and emotionally satisfying conclusion, neatly tying its many seasonal threads and character arcs together. Its three protagonists are sympathetic and nuanced, and while its supporting cast isn’t always likable, they’re just as well-defined and layered as the novel’s stars (and some, like eccentric manchild Oji, are frequently a hoot).

Its female characters develop multiple complex relationships with both men and women; the story honestly depicts sexism and actively discourages the “women as rivals” narrative in favor of collaboration and mutual respect; and it consistently finds ways to balance the professional with the personal, depicting both as important without letting one overshadow the other.

I struggled to get into it, but I turned the final page with a big smile. Anime Supremacy is an informative and thoughtful read that, while imperfect, is still well worth your time and money. Snag a copy if you can.

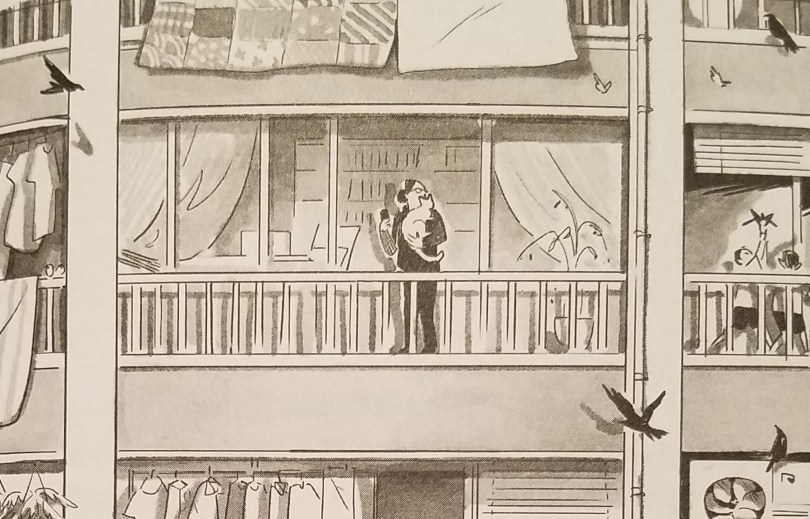

Art by Hwei Lim, from Vertical’s Anime Supremacy! English translation, First Edition (2017).

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.