Spoilers for My Hero Academia seasons 1-4.

Content Warning: discussion of transphobia, parental abuse, police brutality, ableism.

In February of 2020, a Japanese Twitter user created quite the stir in My Hero Academia’s online fandom with their observation that four characters of the property share birthdays with extremist, mostly far-right political figures in Japanese history.

Characters in the story shared birthdays with Adolf Hitler and WWII-era Japanese war criminals, among others. It came straight off the heels of another controversy, where author Horikoshi Kouhei named a villain who conducts human experiments in the manga “Maruta,” a word with strong connotations to the human experimentation that took place under fascist Japan.

This article is not about that.

Given the sheer number of characters on My Hero Academia’s roster, we’d need the ability to read Horikoshi’s mind to discern super secret fascist messaging from coincidence on Horikoshi’s part. Without superpowers (or an official statement), we’re basically playing horoscopes with fictional teenagers.

Instead, let’s ask a far more interesting (and important) question about the story: how does My Hero Academia work? Not in terms of its world building or mechanics, but in terms of the emotional communication of the story.

In a world where 80% of humanity has a superpower known as a quirk, quirkless teen Midoriya Izuku inherits the power of the country’s strongest hero, All Might. He and his classmates at the prestigious UA high school train to become professional warriors for good against the villains who use their quirks for evil.

My Hero Academia, in its proud declarations of right and wrong, good and evil, heroism and villainy, argues how the world should be. Understanding how My Hero Academia works means understanding what this prescription is.

Let’s start with a close reading of one of the story’s most interesting tertiary villains: Hikiishi Kenji, a.k.a. Magne.

What makes a villain?

Magne was a member of the League of Villains, an organization dedicated to the destruction of hero society through acts of terrorism. She’s also one of the only trans characters in the story thus far. She is killed at the beginning of the anime’s fourth season by Chisaki Kai, a.k.a. Overhaul, the leader of the Shie Hassaikai crime family.

In Season 4 Episode 11, Magne is posthumously misgendered by Overhaul and is quickly corrected by Magne’s former teammates Twice and Toga. They refer to her as their big sister and swear revenge for Magne’s death.

While at first it is encouraging to see the gender of a trans character so readily affirmed by sympathetic characters, the buzz of “good representation” wears off fast. Why is it that this character in particular dies a horrible death in a story that tends not to kill its characters? What was Magne even doing before she died? What does she do in the story?

Not very much, it turns out. The lines Magne says right before her death are the first time we get any insight into what she cares about as a character. Before Magne dies in Season 4 Episode 2, she says to Overhaul:

“Sorry about you, smallfry, but we didn’t band together just to serve under somebody’s boot. The other day I met with an old friend. She’s a gentle soul but she supports me even when knowing about my past. You know what she said? ‘Those who are bound by the chains of society laugh at those who aren’t.’ I’m here because I don’t want to be bound by anything! We’re free to decide for ourselves exactly where we belong!”

The “she” Magne mentions (who is disappointingly unnamed) in this quote is another trans woman and, presumably, one of her only friends outside the League of Villains.

According to her own words, Magne fights for her right to exist. She fights with the League of Villains because they’re the only people left in society who will accept her.

Magne’s struggle is the same as the struggle of trans people and other marginalized people who exist in real life: a struggle to tear down society entirely and replace it with systems that support everyone and not just the various small castes of privileged groups at the top. She’s relatively low on the totem pole of characters who deserve karmic justice. We don’t even see her kill anyone.

Of course, having a morally correct villain or morally incorrect heroes isn’t new to popular action anime or superhero stories in general. And of course not every character death in fiction is obligated to be “fair.”

Still, My Hero Academia isn’t exactly a story with grey characters. The text actively rejects moral relativism, if anything. With villains like the Hero-Killer Stain (subtlety: not HeroAca’s strong suit), the narrative actually suggests that understanding villain motivations is one of the most dangerous things about them. After all, if we sympathize with villains, we might give them the room they need to hurt more people.

Without the “out” of being a morally grey antagonist, we must accept that My Hero Academia condemns Magne for her struggle for liberation. She’s a villain, after all, no matter how sympathetic.

What about some of the other villains in the series? Does Magne’s gender make her an unfortunate exception, or is there a larger pattern at work?

Bubaigawara Jin, or Twice (mentioned earlier) has an undiagnosed mental illness. He says:

“And there’s no place in the world where crazy people can belong. Heroes only care about saving good citizens. But the League accepted me for who I am, problems and all. And I’d like to think I’m okay with who I am too. Now I’m scouting people, looking for the same kind of crazy. We’re all wackos looking for a place to belong.”

-Season 3 Episode 24

Toga also struggles with mental illness, describing wanting to live in a world where she’s free to do whatever she wants. League of Villains boss Shigaraki Tomura was abandoned as a child by hero society, only to be picked up by master villain and his future mentor, All for One.

We could keep going, but a good chunk of the explored characters that compose the League of Villains are just marginalized people who have banded together to destroy the systems that oppress them. They’re not all wonderful people – Toga just wants to stab people, to be clear – but what’s key is that they form a justifiable reaction to oppression. Ultimately, the system is the problem here.

That’s not how My Hero Academia sees things though, and that fact betrays an entire string of reactionary politics riddled throughout the narrative.

My Hero Academia sees its villains not as marginalized people fighting for their own liberation, but as social rejects lashing out at society after failing to integrate. As sad and as relatable as these rejects may be, says the narrative, they’re still evil and they still must be opposed with violence instead of met with understanding.

One other troubling observation: all the mental health representation is taken up by characters who are “villainous” or “violent” for fun. Magne’s proximity to the trope makes it even worse – both for pushing incorrect, bigoted assertions about trans identity and mental illness, and that the people most passionate in gendering her are people with mental illness, who the narrative despises.

On Tiger

Interestingly for us, Magne is not the only trans character in My Hero Academia. Indeed, the story gives us not one, but two entire trans characters to analyze (wow!). What’s even more complicated is that this other character, Tiger, is a hero instead of a villain.

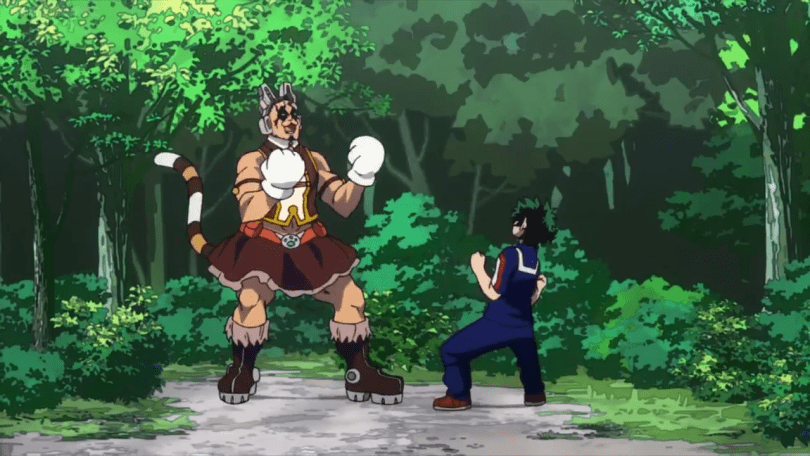

Chatora Yawara, or Tiger, is a member of the pro-hero group the Wild, Wild Pussycats. His quirk, Pliabody, allows him to stretch any part of his body in ways that would normally be impossible. He is never misgendered in the narrative. In many ways, Tiger provides the kind of positive trans representation that may be missing from Magne.

Tiger is unambiguously a hero, through and through, and is admired and respected by the students and pro-heroes around him. The narrative gives us a “good” trans character and a “bad” trans character, almost begging us to compare the two.

Unlike Magne, Tiger’s gender identity isn’t brought up in the story itself. Rather, it’s first mentioned in the manga on a character stat page. Because of this, Tiger’s gender is not mentioned in the anime at all, only the source material.

Tiger’s gender impacts neither the story nor the story’s world. He’s surrounded by the support of a pro-hero team and family that loves him. As one of the founders of the Wild, Wild, Pussycats, he’s a capitalist, who, in addition to doing hero work himself, employs and profits off the labor of smaller heros, secretaries, staffers, and interns. He can afford the trip to Thailand for gender confirmation surgery. Plus, Pliabody allows Tiger to permanently shapeshift his body into a shape more in-line with society’s expectations for masculinity.

Magne doesn’t have these privileges. She doesn’t have the money to leave the country for surgery or hormones. She doesn’t have a rich family who supports her no matter what. Her gender presentation challenges assumptions about gender roles in society. As such, she has no choice but to demand the status quo change for her own survival. And for that, My Hero Academia sees her as a villain and a danger to society.

What makes a hero?

“Here’s the sad truth: all men are not created equal.”

So says Midoriya Izuku in the opening sequence of the first episode of the first season of My Hero Academia. Speaking literally, he is of course correct. Different people, different quirks. Big whoop.

But thematically, there’s a lot more going on here than the simple recognition that people have different powers. Let’s ask a new question: if villains use quirks to destroy society, what do heroes do?

In Season 2 Episode 20, we learn that the story’s ultimate villain, All for One, has been around since the dawn of hero society. His quirk allows him to steal, gift, or combine quirks into new, terrifying powers. He used this power to “bend people to his will” and to commit “evil acts.” What those “acts” were exactly, we’re never told. But boy, were they definitely evil. I promise.

All for One activates a quirk in his much less powerful brother, One for All: the power to pass quirks down through the generations. One for All is the personification of good, a power passed through the ages to All Might and eventually to Midoriya.

As All for One came first, to My Hero Academia, evil comes first, and good is created to beat it. People rob banks or murder, and heroes come around to stop them. This flatly denies the more reasonable (and fact-based) explanation for crime: that people commit crimes because they have to.

To the narrative, it doesn’t matter if you’re poor and starving. If you rob a grocery store, it’s because you were an evil person to begin with, and the system needs to lock you up before you become an even greater threat to society.

The story pretty regularly implies that villains commit crimes for fun and their justifications are flimsy covers for an inherent love for violence and chaos.

Shigaraki: “You think you can get away with violence if it’s for the sake of others… That pisses me off. Why do people get to decide that some violent acts are heroic and others are villainous?… You think you’re the symbol of peace? You’re just another government-sponsored instrument of violence.”

All Might: “You’re nothing but a lunatic. Criminals like you, you always try to make your actions sound noble. But admit it, you’re only doing this because you like it! Isn’t that right?”

-Season 1 Episode 13

Or how this villain describes the days before All Might rose to prominence, driving crime into the shadows:

“Man I miss the days before All Might… Remember when villains were wild and impulsive?… It was a real good time! But when All Might showed up, everything changed and got so damn boring. Can’t have any fun when that pillar of justice is around.”

-Season 2 Episode 18

Legitimate grievances with society in My Hero Academia are mangled and reduced to an itch to destroy for fun. All Might, the “symbol of peace” as he is called, lies at this society’s center. The narrative casts those who want to change society, the villains, as those opposed to the “symbol of peace.” The heroes therefore, beyond their “bravery” or “selflessness,” exist to enforce peace, the status quo, with whatever violence necessary.

Todoroki Enji, a.k.a. Endeavor, the world’s #2 hero after All Might, is a serial domestic abuser. He trapped his wife in a marriage with the express purpose of creating “genetically perfect” off-spring. He abused his wife, neglected his “failed attempts” at children, and beat his successful child, Todoroki Shouto, in hopes that his son would one day surpass All Might.

Endeavor, is, uh, a huge piece of shit. To put it mildly.

Endeavor is granted a redemption arc. The family he abused does not immediately forgive him, but they accept that he’s made an effort to change.

Aside from the inherent insult in attempting to redeem an actual child abuser in a story where trans characters die horrible deaths for the “villainy” of standing up for themselves, the reason Endeavor is allowed to change for the better is simple: he’s a hero.

He still beats up petty criminals; those forces that seek to fundamentally change society. As a pro-hero says of the League of Villains:

“The League of Villains: thugs with a grudge against this world.”

-Season 4 Episode 13

Thin Blue Line

Imagine this: one one side, innocent defenseless people. Your friends. Your family. Your loved ones. And on the other: a relentless evil waiting to rain destruction on it all. Only a Thin Blue Line separates the two, protecting the innocent.

That little line’s name? Law enforcement.

According to this view, parroted by police officers and far-right groups alike (but I repeat myself), the world is made better by killing or incarcerating all the “naturally evil” people in existence. If, say, Black people have worse economic outcomes than other groups, it’s not due to systemic discrimination, but because not enough Black “criminals” are in prison.

To people who believe in the Thin Blue Line, Black people commit more crimes because their “culture” says it’s “fun.” Because they’re just more evil.

“Here’s the sad truth: all men are not created equal.”

To the Thin Blue Line narrative, the real problem is the activists. It’s Black Lives Matter. It’s the calls to do something about the inherent contradiction in the fact that the “freest nation on Earth” houses 25% of the world’s prison population. It’s the media that sows public distrust in the police by… holding them accountable to obvious abuses of power.

My Hero Academia distrusts the activists in its own story. It condemns its press corps for asking questions of its pro-heroes and suggests the world would be better off if the press praised the heroes unquestioningly.

The pro-heroes of My Hero Academia are this Thin Blue Line.

My Hero Academia doesn’t have a problem with trans people existing. It has a problem with trans people inconveniencing the rest of society; with demanding that society change to provide equal access to medical care, housing, and employment; and with demanding that people recognize them for who they are without needing to follow some pre-approved acceptable box of expression.

Out of its misplaced reverence to the status quo. My Hero Academia has a problem with any marginalized people raising hell to make the world better if it inconveniences the hierarchies society is built upon.

And that’s kind of fucked, to be honest.

Editor’s Note: Protesters all over the globe are continuing their fight against police brutality. If you are able, please consider contributing through ActBlue’s Donation Form, which allows donors to split funds “between 70+ community bail funds, mutual aid funds, and racial justice organizers.” Additional resources are available here and here.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.