Spoilers for Josee, the Tiger, and the Fish

Within disability communities, the concept of “inspiration porn”—stories wherein a disabled character exists as a perfect person who inspires abled audiences—is a frequent concern, especially in stories written by abled authors. Josee, the Tiger, and the Fish, a 2020 adaptation of a 1987 story of the same name, is certainly an uplifting and inspirational film, but its treatment of its central character usurps this concept. Instead of being saintly, Josee is a rounded character who works to achieve her dream of living as an artist. Through its titular character, the film Josee, the Tiger, and the Fish navigates the barriers that get in the way of persons with mobility limitations, illustrating their resilience and ability to empower themselves and others.

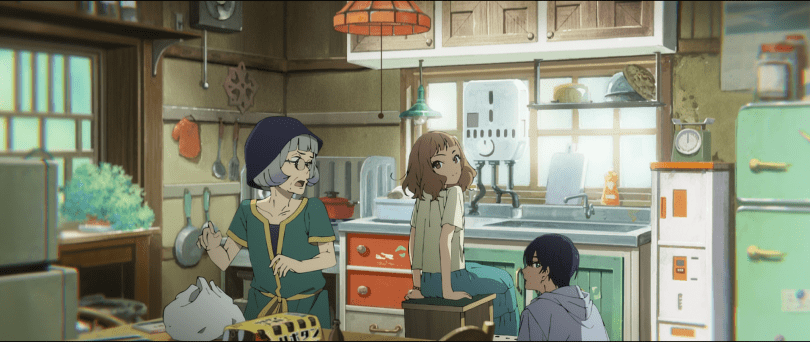

The film opens with Josee, named Kumiko at birth, dreaming of swimming like a mermaid past a school of fish and a blue whale. Reality returns when her grandmother, her sole living relative, shuts off the music. Shaken free of this dream, Josee remembers her life as a wheelchair user—one who cannot easily leave the house without her grandmother. To ease her isolation, her grandmother hires aspiring diver Tsuneo as a caretaker, attempting to assist Josee and ultimately setting her on a path to her own self-determination.

People with mobility limitations, especially those who use wheelchairs or equivalent devices, face numerous social and physical barriers. Some obstacles are obvious, like stairs preventing access into buildings, while others are more difficult to directly address, such as seeking employment and pursuing and maintaining meaningful social relationships. Despite the passage of laws in support of these people, many barriers remain in place, greatly limiting their ability to live independently. Though Japan hosts different mobility barriers from other countries such as the US, there are still key similarities in the efforts to provide persons with disabilities independent living (through economic independence) and free access to society.

As a wheelchair user, I have personally seen many of these obstacles, and more, in both the US and Japan. Upon my arrival in Japan, I could not board the bullet train with my mobility scooter. My father convinced the Japan Railways staff to loan me a wheelchair in exchange for temporarily surrendering my scooter. As a result, I experienced Japan over a few days while in a wheelchair. Like Josee, I got help from attendants to lay out ramps onto train cars. Despite being more mobile than her, I can relate to many of her experiences as a fellow wheelchair user.

Josee elucidates many of the access barriers and other difficulties that wheelchair users face. In fiction and in real life, wheelchair users are often thought of as people who suffered a tragic accident. Instead, Josee is a twenty-four-year-old who’s been unable to walk from a young age, providing a less-explored angle. She also makes use of adaptive behaviors such as using her hands to move herself without her chair, highlighting her ability to maneuver around barriers. Unfortunately, these adaptive behaviors are not enough to overcome many challenges faced by wheelchair users; because of this, her grandmother hires help.

For much of her life, Josee was unable to leave her house. Tsuneo’s support finally gives Josee the opportunity to leave the house regularly. Now emboldened, Josee begins her movement towards independence by requesting a trip to the ocean, which she saw only briefly as a child.

Despite her knowledge from books, Josee does not know how to get to the ocean, presenting a clear access barrier. She gets stumped by purchasing train tickets at the station. Seeing her frustration, Tsuneo helps her by securing the tickets and then requesting the help of an attendant to lay out a ramp. This demonstration helps Josee learn how to navigate transit on her own, setting her up to take a solo trip later.

Once finally at the beach, Josee excitedly wheels her way onto the sand before facing resistance and getting stuck. To keep moving forward, she resorts to rocking her chair and ends up landing on the beach. Undeterred, Josee crawls towards the water, conjuring the image of a wheelchair user fighting against an inaccessible world. With great excitement, she exclaims that the ocean is salty, cementing the physical experience of her trip. Here, she sees her aquatic-themed art come to life in the ocean itself, giving her courage.

Josee begins the process of reclaiming her life for herself. In support of her newfound motivation, Tsuneo creates a short staircase, allowing Josee to cook independently. While Tsuneo facilitates her transportation, Josee is the one who shows the strength to reach out, challenge herself, and make connections. With her caretaker, Josee next sees fish swimming freely—a clear reminder of her dream of mobility.

Their next stop, the library, gives Josee the opportunity to become part of a fully public community. For the first time, Josee is able to see many people in one place with a similar purpose, and Josee befriends the librarian in the process of getting a library card. Through this connection, she is able to pursue her burgeoning interest in art. While she still faces challenges and is still clearly building confidence, Josee gains more autonomy over her time and her passions.

The unexpected passing of her grandmother leaves Josee with a small sum of money, placing her in a precarious situation. A social services representative dismisses Josee’s desire to pursue art and lectures her about pursuing realistic employment like a monotonous desk job. Through social services, Josee is able to procure an electric wheelchair, offering greater freedom of movement than her manual wheelchair. However, though a desk job provides economic security and greater independence, she finds herself cut off from a meaningful community. Josee, as the film asserts, cannot lead a full life under these circumstances.

Another film adaptation of the story was made in 2003, and it does not imbue Josee with artistic ambition or the nuanced quest for autonomy and community that rests at the heart of the 2020 version. Instead, at the start of the 2003 film, Josee is pushed around in a humiliating shopping cart, offering very little independence or dignity. In this iteration, Tsuneo still acts as her caretaker, and her grandmother still passes away. However, her relationship with Tsuneo is largely presented in romantic terms. When they break up, at the end of the film, she transitions to an electric wheelchair. Because Josee’s interactions are largely framed through romance, this gives her a false independence without meaningful relationships.

Josee, in the 2020 version, almost falls into the same trap: after her grandmother’s death, she fires Tsuneo as her caretaker and seems to passively accept her circumstances. Instead of pursuing art, she takes on a meager office job at the insistence of the social worker, which makes her increasingly frustrated. Eventually, she calls Tsuneo to meet her at the ocean. Tsuneo, who is chasing his own dreams of diving in Mexico, begs her to continue pursuing art.

Josee rejects his statement precisely because he is able-bodied and wheels away. Shortly after, a fierce downpour traps her on a busy road. Tsuneo rushes to shield her but is struck by an out of control car and sent to the hospital. There he learns that he sustained a major injury to his knee, which may prevent him from walking ever again, let alone diving. As a result, he is compelled to consider Josee’s perspective within the context of his own body, which is rare for able-bodied people to fully appreciate. At the hospital, Josee realizes that Tsuneo is now facing the same passive despair that he had helped her through. Seeing Tsuneo in this state inspires Josee to share her dreams with him. She goes to his dive shop job and arranges for Tsuneo to be wheeled to the library, in a reversal of her first outing there.

To inspire Tsuneo and those around her, Josee assembles the community she built. Through her librarian friend, Josee organizes a picture book reading time—for her own book. This coordination, done entirely without Tsuneo, reveals her devotion to art and to community. There is a gulf between her first and second readings at the library: this time, Josee is confident in her work and herself and everyone is enraptured, highlighting her growth.

Through this activity, Josee is able to genuinely inspire her community through devotion to her craft. Buoyed by her performance, Tsuneo wrestles with walking bars, completes his rehabilitation, and pursues his dream dive in Mexico. Instead of simply handling barriers, Josee inspires others to overcome their own challenges. This presents an interesting spin on “inspiration porn”: Josee is inspiring Tsuneo and her new community, but she actively takes control of her narrative and realizes her artistic dreams in the process. This journey is about her own arc as much as it is about them.

Josee, The Tiger, and the Fish illustrates how wheelchair users, whether lifelong or temporary, face great access barriers but can find ways to empower themselves and others. Through the support of Tsuneo, and others, she pursues this ideal through ocean-themed art while growing in her self-agency. Josee inspires a similar confidence in others through her picture book reading, helping establish her own compassionate sense of community. The twinning of Tsuneo’s narrative with Josee’s grows the expected narrative of “inspirational” disabled characters into one where Josee becomes a fully developed character, one who inspires others with her art rather than being treated as an object lesson.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.