CONTENT WARNING for nudity and discussions of sexual harassment. SPOILERS for events in Made in Abyss Episodes 1-9.

Made in Abyss is frequently one of the most breathtaking shows of the season (you might recall Dee’s glowing premiere review), juggling gorgeous cinematography and dark fairy tale elements with a grim but (thus far) not hopeless narrative.

Its young lead, Riko, is an endearing sometimes-crybaby who never gives up or lets her fear get in her way; and the show has also played with gender fluidity, featuring two nongendered characters whose designs contrast feminine-coded presentation with masculine-coded pronouns (a shy child who wears dresses and uses the politely masculine “boku”; a fuzzy bunny-person who wears pink and uses the casually masculine “oira”). Even when it’s frustrating, I’ve never wanted to tear my eyes away.

Unfortunately, it’s also a show whose flaws are all the more glaring in comparison to its moments of excellence. Discussing those flaws offers a unique challenge, however, as many of the show’s failings are cloaked beneath a layer of in-narrative justification; in other words, it makes sense on the surface as to why these things are happening in the plot. But no media exists in a vacuum, and justifying a trope doesn’t stop it from playing into broader harmful trends.

You might have heard of the issue of in-narrative versus meta-textual justification as applied to fanservice, where someone says “but the character CHOOSES to dress like that!” in response to critiques of a character’s design. And that may indeed be true. But fiction isn’t real—a fictional character thinks the way they do because someone wrote them that way, usually with an audience in mind. More broadly, worlds and plots happen because the author designed them that way.

This is easier to point out regarding fanservice because of the logic behind it. Plenty of articles have already been written on sexual objectification, the male gaze, etc. (including on this very site)—things that are embedded into a culture at an unconscious level and can influence a writer even if they aren’t thinking about it. Sexualization in media is visually apparent to the layperson because generations of critics have worked to expose that connection.

When it comes to larger storytelling beats, troubling elements tend to fly more easily under the radar because they’re baked into the world and narrative. The story agrees with itself in a more self-sustaining way than a strongly visual element like fanservice (and viewers are often already attuned to understanding visual language anyway, even if only unconsciously), so stepping back to the meta level is something a person must train themselves to do.

For example, let’s say a story kills off its only lesbian character. Perhaps in the story she’s naïve and in over her head, and the story foreshadows that this is a possible outcome. It’s well-structured on a purely narrative level. But stepping back, this story would exist alongside many, many other stories (with various levels of quality writing) where gay and lesbian characters are killed either as “punishment” or to imply that their existence is tragic. All media exists in conversation with other media, and it’s something creators and viewers must be aware of when interacting with stories.

The first troubling element of Made in Abyss is, at least partly, a visual one. The show’s protagonists and a large chunk of its cast are prepubescent children, and one of the anime’s themes is that these kids are growing up in a harsh and unforgiving world. Part of that includes the decision to show young characters nude.

This is far from unheard-of in anime, and there are arguments to be made for desexualizing nudity, as seen in familial contexts like My Neighbor Totoro or even absurd comedic series like Dragon Ball or Crayon Shin-chan. In theory, Made in Abyss could justify its nudity as its young protagonists fight to survive in the wild. But framing and context are king, and it’s what makes the show’s choices troubling.

Part of Reg’s character introduction, for example, is discovering that in addition to his robotic limbs he has human genitals. The small, initial moment of discovery is shown only through his reaction, with no one else around, and it’s believable for a character at that age to be both embarrassed and fascinated. Credibility is strained somewhat by then hammering on the same beat multiple times as the other child characters (including Riko) are fascinated by this aspect of his anatomy. It’s repetitive, but again it’s not shown, and all the characters are children.

Any justification goes out the window when Reg is later grabbed by an adult character who opens his pants to look at his genitals. Reg is clearly embarrassed, but it’s played for comedy anyway, and perpetrated by an adult character we’re meant to read as helpful and trustworthy. It’s hugely uncomfortable and exploitative, and transformed my wariness into active mistrust of the narrative’s handling of its child characters.

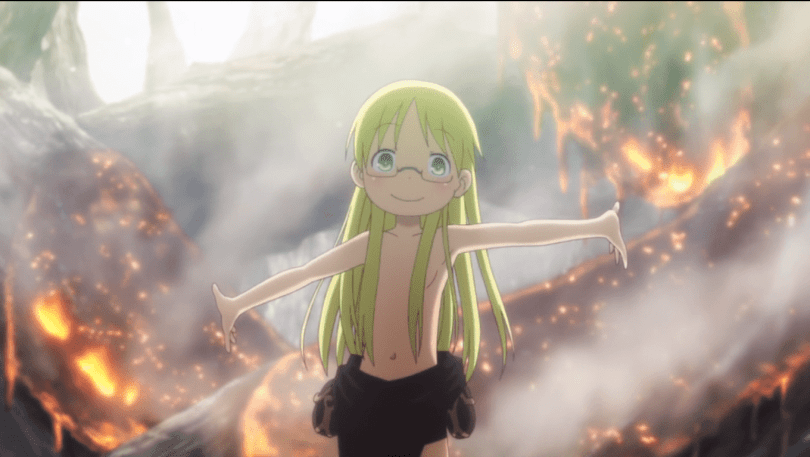

Things are worse regarding Riko. While jokes are made at Reg’s expense, it’s invariably Riko who has to get naked for plot reasons. In isolation, some of these moments would arguably fall under believable nonsexualized nudity—Riko spends one scene shirtless, for example, because she vomited on her shirt and had to be stripped while unconscious in case she was in medical danger. That her hair falls over her chest in the same way it would if she had breasts would be odd but not alarming.

But that dire need for nudity, invariably only in Riko’s case, keeps coming up. In the first eight episodes, four show her fully or partially nude. The sheer quantity dilutes the argument that it’s done for narrative impact and push it more towards fanservice—particularly when the nudity involves an element of humiliation, as when the series depicts the societal punishment of “stringing children up naked.”

This is referenced as a painful, horrifying punishment in dialogue, but when we see Riko being punished it’s during an otherwise lighthearted montage; and while the camera shows relatively little of her body, her wriggling shoulders and blushing, humiliated face are in the forefront of the frame.

Nudity is a difficult subject, especially as sexualization (of female characters in particular) is applied to younger and younger characters. Likewise, while Made in Abyss primarily uses its moe aesthetic to contrast its innocent protagonists with the horror of its setting, there’s also a long history of moe intersecting with lolicon that we need to take into account.

Finally, there’s the prominent use of humiliation for sexual titillation in hentai, a piece of visual coding that affects viewers’ perceptions even when they’re watching non-pornographic works. These historical influences and bits of established coding come together to make Made in Abyss’s nudity uncomfortable at best and outright exploitative at worst.

The show’s other problem is tied to gendered tropes. Riko is a skilled forager, but this is depicted mostly as her always doing the cooking (over stew pots whose contents look remarkably like domestic, modern Japanese cuisine despite being scavenged from caves and burrows). We rarely see Riko catching or killing food as the series goes on, and the framing instead depicts it as a domestic activity, as if they’re taking a leisurely camping trip rather than surviving.

While the impetus for the story is Riko’s desire to become like her mother, a capable adventurer, other characters are constantly telling Reg he needs to “protect” Riko (but Riko’s never told to protect Reg). Initially, it seems like the series is going to address this imbalance in Episode 9, “The Great Fault,” when Riko has to both look after Reg while he’s unconscious and find a way to survive on her own. The majority of the episode is by-the-numbers, developing Riko’s character while also enforcing the idea that she and Reg are better as a team.

However, at the climax of the episode, as Riko grabs her mother’s axe and prepares to stand up to a large monster, her heroic moment is stolen from her. The narrative events leading to this scene make it believable that she can win, as the axe is a distance weapon and the monster is already wounded and close to a cliff. But just as she’s about to fight, Reg wakes up and defeats the monster—and uses Riko’s own mother’s axe to do it.

It’s almost offensively anticlimactic, rendering Riko’s progress over the course of the episode moot. Her ingenuity and determination, which are meant to be a core strength, are disregarded in favor of letting Reg save the day once again. This element could’ve conceivably worked if the two had taken down the monster together, furthering the story’s theme of teamwork, but instead Riko is forced into a passive role at the last minute.

Like the extreme cases of nudity, this obvious beat of narrative sexism is an outgrowth of the gendered traits displayed earlier in the story. And while the series pays lip service to the pair being a team, it’s Reg who’s coded as both the physically strongest as well as most reasonable character (while Riko is enthusiastic and theoretically has the most background knowledge, Reg still gets to ask the most pertinent and incisive questions during periods of exposition).

Saying two characters are equal doesn’t mean much if narrative execution doesn’t bear it out. While we were told this was Riko’s story, she’s getting to do less and less of importance as time goes on (it also doesn’t help that as the amount of nudity recedes, an emphasis on Riko’s suffering takes its place, shifting the commodification of her body rather than removing it).

The manga is ongoing, so the series could still resolve this issue and get itself back on track, but it’ll need to pay careful attention to treating Riko and Reg as an equal team rather than paying lip service to the idea while positioning Reg as the actual, active hero.

It can be easy to take a story at face value if it avoids plot holes and hooks you emotionally. And it’s true that Made in Abyss has a thematic backbone behind several of its narrative choices: because Riko is a human and Reg a robot, Riko’s journey often coincides with fears of mortality while Reg’s journey examines the meaning of emotional “humanity.”

These themes are coherent and considered within the story, but they only “have” to be that way because it’s what the author decided to write. The story would feel quite different if Reg and Riko were the same gender, or even if their genders were reversed. There are far fewer stories about physically fragile men undergoing grueling physical and psychological torment while their stronger female companions anguish about not being able to protect them, after all.

No story exists without context, and no character decides to do something without an author wanting them to do it. Small, seemingly unimportant decisions can grow into a mindset that affects how the plot progresses, like Riko going from needing to be “protected” to losing her chance to act as the hero. And things that could be harmless when employed with restraint (like nudity or suffering) can become skeevy depending on how they’re framed and how often they’re utilized.

It’s worth critically examining story logic and seemingly minor elements, because if those elements are reflective of the creator’s biases (conscious or unconscious), they can grow from background noise to active influences on the plot.

Made in Abyss is, by and large, a well-told story with compelling characters and visuals; and of course no media is free of flaws and troubling elements. Problematic narratives can and often are nested within shows that have good writing—it doesn’t make the series automatically worthless, but neither does it mean those problems should be ignored out of fear the good things will be overlooked.

Both are important. Both deserve consideration. That kind of messy nuance is where the best and most productive progress lives. Like the abyss, great ventures mean great risks, great horrors—and, sometimes, great rewards.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.