When I was growing up in the ’90s, there was a single popular narrative of kids with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Their lack of impulse control caused them to be so loud and disruptive, the only choice was to drug them so others around them could function.

They exasperated their teachers and distracted their classmates. They were smart and creative, but never in productive ways. If they were funny and well-liked, they were class clowns; if they weren’t, they were the weird kid who everyone wished would just shut up and go away. They were always, always boys, like Bart Simpson and Calvin of Calvin and Hobbes. Most importantly, kids with ADHD would sooner or later grow out of it, eventually ceasing to need their Ritalin or Adderall and just become functional adults.

I never heard anyone with the condition talk about what it was like to have it, and the way people talked about children with ADHD—emphasizing just how hard they were to deal with—made them sound almost willfully malicious. It never occurred to me, or any adult in my life, that the girl who read books under the desk and didn’t turn in her homework because it was crushed at the bottom of her backpack could possibly have the same condition associated with out-of-control “problem children.” All the problems I had with punctuality and focus were personal and moral failings stemming from laziness.

But then, in my mid-20s, when my now-husband told me about the symptoms of his ADHD-PI (primarily inattentive), everything clicked into place.

The cultural narrative around my condition had long been controlled by outsiders, people who only saw the stereotypical behavior and reiterated and echoed it through jokes about being distracted by squirrels. In the introduction to her manga My Brain is Different: Stories of ADHD and Other Developmental Disorders, Monzusu describes a similar arc. Although she’d always struggled socially and academically, she never really knew why until she started researching symptoms of what the Japanese psychiatric community terms “developmental disorders,” including ADHD and autism, after a doctor diagnosed her child.

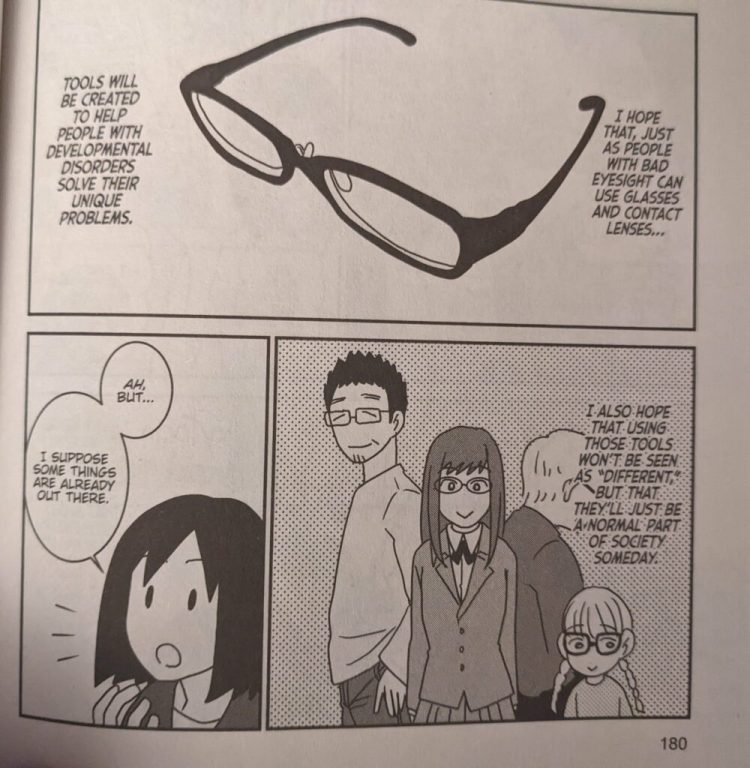

When she realized how poorly understood these conditions were by the general population, she sought out the stories of ordinary people with experiences similar to her own, eventually turning some of them into a memoir manga. In doing so, she offered neurodivergent people like her a rare chance to tell their own stories in their own words, when most of the world would rather talk over us, and created a tool to help people understand people like us.

The English edition of My Brain is Different starts with a note from the translator, Ben Thretheway, about the terminology used throughout the book. Some of the stories in it are years old and use outdated language like “Asperger Syndrome,” which ceased to be a formal diagnosis in the US in 2013 in favor of being folded into the broader diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The term has come to be disliked by members of the autistic community because it sets up a false dichotomy between mild and severe autism, and because the doctor it was named for, Hans Asperger, was a Nazi who sent thousands of children to their death.

Even the use of the word “disorder” invites controversy, because of the growing perspective that autism and ADHD should not be considered a disorder, but rather a difference that is neither better nor worse. Still, the manga retains the language because the narrators have the right to tell their own stories in their own words and choose their own labels, because their experiences are valid and not open to being “corrected.”

The importance of allowing neurodivergent people to speak in their own words stems from how, historically, we’ve had little opportunity to represent ourselves and our experiences. Monzusu describes how she found the language in her research stigmatizing, and how worried she felt about her child’s future. If few people on the autism spectrum, with ADHD, or with other developmental disorders are able to give their own perspective, then naturally their experiences will be filtered through the lens of neurotypical society, often into little more than a list of inconvenient symptoms.

In the US, this effect is visible in a number of supposed advocacy organizations such as Autism Speaks, the largest such in the US. They have been widely criticized for funding research for a “cure” for autism, which treats it as a disease; perpetuating the myth that vaccines cause autism (though they seem to have reversed this position recently); and spending only a tiny fraction of their budget on supporting families with autism while over half goes toward fundraising and lobbying.

Nearly all the resources on their site are dedicated to helping families cope with a diagnosis, rather than speaking directly to autistic people, often with fearmongering language. One of its executives even described a fantasy where she would put her autistic child in the car and drive off a bridge.

When encountering autistic people in real life, its representatives behave in ways that work to further marginalize them. Anime News Network forums user HnoT described his daughter Plutan’s encounter:

When she pointed out that they didn’t seem to do nearly as much as other organizations after informing them that she had ASD, the people started banging on their table, becoming physically confrontational (with direct eye-contact too) and raising their voices yelling that those with ASD can become dangerous.

This was an obvious attack to generate an outburst response to validate their point in front of the other interested people at the table. My daughter held out and informed the others of what the canvassers were attempting to do.

That’s the biggest autism advocacy charity in the country. Is it any wonder that autistic people feel spoken over?

In allowing people with developmental disorders to tell their own stories, Monzusu sidesteps the temptation to follow tidy narratives or devolve into inspiration porn. Most of her subjects, like herself, weren’t diagnosed until adulthood and up until that point, never had answers for why they struggled so much with basic tasks or could never seem to fit in.

These are not tales of heroically overcoming the obstacles and odds, because that’s not what having an undiagnosed developmental disorder is like. Getting a diagnosis is more like a rush of relief as you find an answer to the hundreds of questions you’ve always had about yourself, most of which you assumed stemmed from some kind of moral failing, mixed with concern and eagerness for the future.

There are so many aspects to ADHD and autism, positive and negative, that no fictional character created by a neurotypical writer for a neurotypical audience could ever hope to capture, in subtle habits and tendencies and ways in which we experience the world that are barely invisible outside of our heads.

A few series, such as the drama Under One Roof and the manga Boys Over Flowers, treat autism as something that develops as a result of trauma, or can be grown out of. Some fans might connect to characters by reading them as sharing their diagnosis, such as Osaka from Azumanga Daioh being a walking checklist of ADHD-PI, or Haruka from Free! showing mannerisms that are commonly associated with the autism spectrum, but accurate canonical representation is rare in popular culture.

Living with conditions so poorly understood by outsiders is difficult. In My Brain Is Different, some people, like Matsubokkuri-san, never manage to fit in and, despite being extremely intelligent, are plagued with symptoms like executive dysfunction that affect their ability to perform the day-to-day tasks that allow them to fit in. They even come to the point of causing harm to their loved ones. Others, like Mamu-san, learn to mask their symptoms, but drive themselves to exhaustion trying to hit what most people consider the bare minimum.

One of the consequences of allowing people to speak in their own words is that there are stories where, even though we share the same condition, I struggle to understand the narrator’s perspective. Iku describes how it feels once the ADHD medication Strattera starts working. Her head feels clearer and she’s able to function professionally, but her emotions feel muted and she’s largely lost interest in most of her hobbies. Despite the disadvantages, she feels positive about her experience with Strattera.

During my brief attempt at taking Strattera, I had similar side effects, which to me put it squarely into “not worth it” territory. I hated the sensation of my passions and emotions being dampened. Horrified at the idea of living like that long term, I insisted on going back to stimulants.

Regardless of my own feelings on the matter, Iku’s experience and priorities are just as valid as mine. This could even be culturally informed; in Japan, Strattera is the first-line medication, with the only alternative being Concerta if the Strattera doesn’t work. All other forms of stimulant medication—Adderall, Ritalin, and Vyvanse, which are popular options in the US—are illegal.

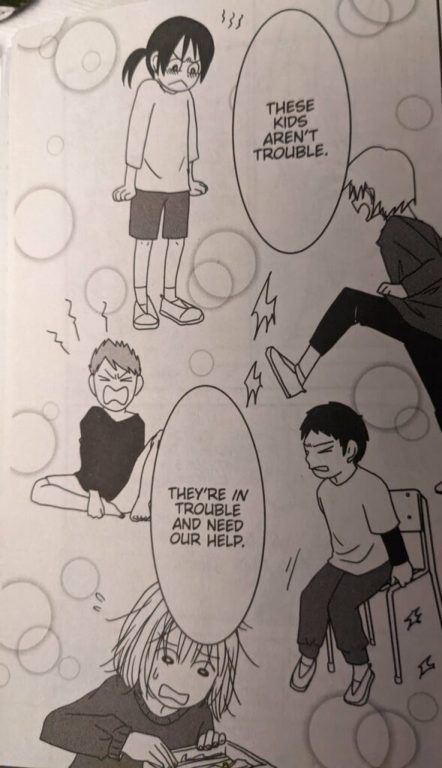

Although most of the stories are narrated by those with the disorder themselves, there are a few stories from the perspective of neurotypical family members. However, the stories still center on learning to meet the needs and understand the experiences of their neurodivergent loved ones. This stands in contrast to most mainstream narratives, which center on the frustration and inconvenience of dealing with a neurodivergent family member.

Cat-Paw Punch tells about how her husband Yuuto struggled with an adjustment disorder after the birth of their daughter, and how she learned to balance both of their needs. Although she admits she was exhausted for a time as she tried to juggle everything and fix their relationship, she still decenters herself as she describes Yuuto and their daughter’s conflicting needs, and how she learned to help reconcile them. She also doesn’t make excuses—when Yuuto hits their daughter, she lets him know that is unacceptable, and if he ever does so again, she’ll divorce him without hesitation.

In another story, Hanako describes her concern for her autistic son Tarou and how his social difficulties led to a rough experience in school until he had a teacher who built a supportive atmosphere in the classroom. At Tarou’s middle school graduation, she was surprised to realize her son wasn’t just getting by, but flourishing as his classmates all asked to take pictures with him.

She narrates how she watched Tarou grow and how those around him accommodated and assisted him with clear-eyed realism, neither falling into pessimism for his future nor stubbornly denying that, sometimes, the world is not understanding to people with developmental disorders.

Despite its simplicity, My Brain is Different has profound potential to help people with developmental disorders feel understood. While reading it, I often wept at recognizing my own experiences reflected so clearly on the page.

To me, the most powerful moment was when Yoshiko, starting work as a teacher at a preschool for children with developmental disorders, realizes that she can help offer these children the understanding she always longed for. I’ve started lending my copy out to others I work with in my own life as a preschool teacher in hopes it will help the colleagues I work most closely with understand who I am and my needs, and the needs of many of the children we work with. My Brain is Different may not revolutionize the world, but it has a chance to make a difference in its own small, quiet way.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.