CONTENT WARNING: This article discusses some games and tropes that include mentions of abuse, along with physical and sexual assault, which are not described in detail.

In the world of video games, anything is possible. You can be a hero, a villain, the mayor of a town of animals. You could, in fact, be a cavegirl dating pigeons in a post-apocalyptic romantic dramedy, or someone helping humanized swords fight against historical revisionism, or you could even be a gender-nonconforming barista at a cat cafe.

In other words, you could be playing an otome game.

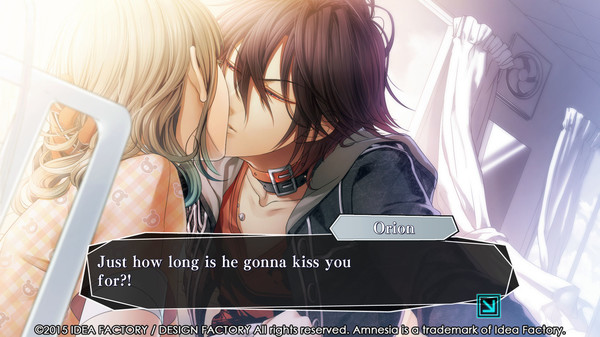

Otome games dive into and privilege the romantic and sexual desires of women. While primarily focusing on and being targeted to heterosexual, cisgender women, there’s been a rise in LGBTQIA+-friendly otome games in recent years. While originating in Japan, with famed developers such as Idea Factory’s Otomate imprint, otome games can come from anywhere, as evidenced by Korean developers such as Cheritz or American developers such as GB Patch Games.

Ever wanted to learn more about otome games? This article is where you can start.

Common Route: History of the Genre

Otome games (乙女ゲーム), literally translated to “Maiden’s Games,” are a unique subgenre that buck male-oriented trends found throughout gaming culture at large. These games are narrative-based over gameplay-based, can be any genre, and are primarily made by female teams with a female audience in mind.

Sometimes called “otoge” for short, these games share genre conventions with bishoujo or gal games, dating simulation games meant for a heterosexual male audience, which began to gain prominence in the late 1980s. However, not all otome games are dating sims.

The main signifier of an otome game is that they contain a cast of handsome men (bishounen)—and, for some, gorgeous women as well. In fact, some prefer to refer to otome games as bishounen games. Romancing is optional, but heavily implied at the least. Still, above all, the story within otome games is key, and because of that, many otome games are visual novels. So, more simply put, dating sim otome games are choose-your-own-adventure romance novels.

The first otome game was Koei Tecmo’s Angelique, developed by Ruby Party (SNES, 1994). Game director Keiko Erikawa, when discussing why she spearheaded Angelique and had a primarily female development team, explained that when she had first began production on the game in 1983: “Games were seen through men’s eyes. That’s when I came to think, ‘I’d like to create games marketed toward women for women.”

She also felt that if it was being marketed toward women, it had to be as aggressively feminine as possible in order to most effectively reach her target audience.

“The protagonist had to be a cute girl and her clothes had to be red. The interiors should be girly and pink… Then, because we wanted to have all sorts of lovely men appear in the game, we set the theme as Greek myth and created male characters with a ton of individuality.”

While Angelique ended up being a resource management sim and not a visual novel, its art is clearly influenced by late ‘80s and early ‘90s shoujo. In catering to an underserved demographic, this labor of love kickstarted the Angelique franchise, which became a smash hit among female gamers in Japan but hasn’t found much popularity abroad. It took 10 years, helmed by a team that had little to no prior game development experience, but the Ruby Party women delivered and created a new genre in the process.

Even if the femininity within otome games is oftentimes normative, the genre had to start somewhere. It also had an uphill battle considering the greater gaming culture it was engaging with. Male-targeted bishoujo games, which were often disparaging to women, were quite popular, and mainstream games intended for heterosexual women—and romance games, to boot!—were a rarity.

To be a frilly, “girly” romance game and fantasy resource manager was unheard of at the time. Even now, a game like Angelique would not necessarily be common. Over time, however, otome games began to evolve to include more diverse portrayals of femininity, and even masculinity and nonbinary identities.

“Deep Story”: Popular Tropes & Structure in Otome Games

There are plenty of standard tropes that apply to the genre. While many overlap with shoujo, some are unique to otome games. Since most otome games are dating sims, I’ll mainly be referring to those, but these ideas can also apply to non-dating-sim otoge.

Structurally, otome games tend to have multiple story paths and endings, referred to as “routes,” which allow players to pursue a character romantically. In otome games without romance as the main gameplay component, there is more flexibility, but the “choosing” aspect is still there when players are allowed to pick characters, such as in Uta no Prince-sama (UtaPri) and Touken Ranbu. Some dating sim otome games, like Cheritz’s Nameless: The One Thing You Must Recall and Mystic Messenger, format the game into a “Common Route” and a “Deep Story,” where the darker elements of the plot are gradually revealed.

There are also a plethora of endings: Often a good, bad, and neutral ending for each dateable character as well as no-romance/neutral or bad endings. Almost every otome game out there has a super dark or tragic backstory, which is hinted at and then outright discussed throughout various routes within the game.

This usually culminates in a “True,” “Deep,” “Golden,” or “Secret” Route. No spoilers here, but the “True” Routes can really make what was seemingly a frivolous dating sim into a surprisingly riveting drama. These True routes, being darker and oftentimes containing horror elements, are also the source of many a bad ending.

Because of the abundance of endings in otome games, “save scumming”—making multiple save points before a decision so you don’t have to replay the game after you get an early/bad end—is a common gameplay strategy. Trust me. Save your game as often as you can. You’ll thank me later.

The “female gaze” (as it’s colloquially called) is very prominent, due to the presumed female audience. The feminine-inclined cousin to the infamous “male gaze,” the “female gaze” objectifies male characters in a sexual manner. So, where the male gaze would focus on a woman’s breasts or undergarments instead of her face, the female gaze would focus on a man’s abs or muscular arms. For an American live-action example of this, think of Magic Mike. There are anime versions of this too—most infamously, Free!

Shirtless boys, romantic situations, and so on—all of that fanservice is in full swing, for better or for worse. Because of this, as a form of fanservice in and of itself, there are plenty of character “types,” all of which are found in anime and manga as well, but some of which are found in higher frequencies within otome.

Within these “types,” there’s the classics: The Megane (glasses boy), the Princely type, the Cute Type, the Childhood Friend, the “hot foreign exchange student/royal/expat” type, the Mischievous type, the playboy, the mysterious type… the list goes on. Along with that are the various -dere types, which share the aspect of being “cold / cruel / standoffish / etc. on the outside, sweet on the inside…” At least, for the most part—but more on that in a moment.

However, even with the “greatest hits of anime character types,” the most common character type in otome dating sims is the yandere. According to scholar Michael Kroon, yandere comes from the verb “yanderu” (病んでる), or “to be ill,” with the implication of mental illness. Unlike these other types, yandere are the opposite of the traditional –dere character format, with a deathly twist: “Sweet on the outside, murderous on the inside.” This character type also usually overlaps with the “cute” type.

While many examples in the popular imagination of anime fans are female, such as the entire cast of Higurashi: When They Cry, Doki Doki Literature Club’s infamous Monika, or Future Diary’s Yuno Gasai, in otome games the trope is independent of gender, like all other -dere types.

In earlier popular examples of yandere, such as Higurashi, much of the shock factor came from the fact that the adorable, female cast was doing harm to male protagonist Keichi—and between young women and girls too, to boot. The heteronormative, gendered power dynamics common in horror are flipped. That’s part of why female yandere are so scary to the presumed male audience.

However, in games made for women, this gender dynamic becomes a bit more… troubling, to say the least, due to already existing patriarchal power structures worldwide. Unlike in Higurashi and games of its ilk, the trope is romanticized within otome dating sims, where at least one male character is most likely going to be a yandere.

Heck, entire dating sims are filled with a cast of yandere—Nameless has some grisly endings due to the fact that most of the boys in the cast will likely murder the protagonist, or even drug her and assault her. Sometimes the protagonist is yandere as well—in one route of Nameless, the protagonist is heavily implied to assault or hurt Yeon-ho, the “cute” character.

The famous historical drama Hakuouki has a cast that is also comprised of yandere for plot reasons (no spoilers here). Hatoful Boyfriend has its own yandere, the most obvious example being the school doctor, the partridge Iwamine Shuu. Similarly, games like Boyfriend to Death build their entire premise around framing the love interests as dangerous threats the protagonist must survive.

As you can see from these examples, yandere as a trope oftentimes intersects with dubious consent, gaslighting, and/or other kinds of emotional abuse. This character type is a fixture of the genre—but can also be easily avoided if it isn’t your cup of tea, especially with the help of game guides.

Now, of course, you may not be able to get the true ending for some games because of this (Hatoful comes to mind again, requiring you to date the homicidal partridge to get the true ending). But after all, it’s all up to you as the player.

While I love this genre with all my heart, it definitely has some elements that are problematic, as seen above. Even without yandere, dubiously consensual sexual encounters are also quite common in some of the more adult titles.

Some otome games also fetishize same-sex male relationships between the cast members for a heterosexual female audience, in a manner akin to the worst of BL. Some otome scholars (myself included) consider BL games to overlap with aspects of the otome genre due to the audience, history, and tropes that they share—but that’s an article for another time.

Even so, I still find myself coming back to the genre. It is my guilty pleasure. Otome games contain what I love about shoujo and josei manga, but with the interactivity of video games as a form. They have complex stories that are worth the emotional payoff, romantic or otherwise.

These games, in a manner similar to watching The Bachelorette or a (reverse-)harem anime, give players an outlet to explore their romantic, emotional, and sexual desires, in a space unfettered by the societal dangers and stigmas so often attached to dating. Sometimes they’re dramatic; sometimes they’re a welcome, frilly escapist fantasy. In terms of visuals, the character designs are often to die for, and the concepts in many of these titles are unlike anything else seen in gaming.

Most importantly to me, however, they’re a form that gives female characters agency, owning with aplomb what is often thought of as shameful: Femininity.

Golden Ending: Otome Games Now & Beyond

There hasn’t been much academic research about the otome genre since many of the games are erotica or romance fiction, created by and for presumed-straight women. Or, in other words, these aspects of otome lead to gendered bias against it in terms of genre, format, and audience.

I specialize in otome game studies, gender studies, and new media studies, and devoted my undergraduate thesis to defining the genre and just what makes it so special. But, I’m not alone: Recently, otome games have become more and more popular in the West and worldwide. The “Otome Armada,” as the fans call themselves, is alive and well on social media.

In terms of popular games, Mystic Messenger ended up being an internet phenomenon, as did Hatoful Boyfriend. Steam has even picked up some otome games, but they are not remotely as covered within gaming journalism as some of the licensing choices made by Mangagamer and other developers. However, Mangagamer is also licensing more otome, yuri, and BL titles in recent years, so there is hope yet.

The otome genre was one of the few lifelines keeping the PlayStation Vita alive (good night, sweet Vita), but luckily, the Switch, PlayStation, PC, and even mobile are getting ports and new titles from AAA and indie developers. Aksys, as well, deserves a mention for continuing to localize many of these titles. Yay!

There’s also been growing diversity within the otome genre in terms of developers, romance options, and characters. While they are Japanese in origin as a genre, there have been plenty of titles made by non-Japanese developers.

Cheritz’s Mystic Messenger features a female romanceable option, the incredible Jaehee Kang (Pray-hee for Jaehee, everyone)—which means that the protagonist is bisexual! Mystic Messenger also has a surprisingly nuanced portrayal of depression in the forms of Yoosung and Seven, and while it is nowhere near perfect, it’s definitely a start (even if Yoosung is a yandere in his worst routes).

American developers have also created games that are explicitly LGBTQIA+ themed and inspired by otome tropes, such as Hanako Games’ impressive catalog, the smash-hit Dream Daddy, and Christine Love’s work in Analogue: A Hate Story and Ladykiller in a Bind. Date Nighto’s purrfect-ly wholesome Hustle Cat goes a step further by offering pronoun, skin tone, and gender presentation options which have no impact on the romances in-game.

Also deserving of a shout-out are Batensan and their “Magical Otoge” games and GB Patch’s work as well, such as their in-development polyamorous otome game, Floret Bond. Oh, and of course, who can forget one of the games that I’m awaiting with bated breath, Boyfriend Dungeon?

In this post-Gamergate world that we live in, otome games created by marginalized creators with marginalized audiences in mind are all the more important. To play an otome game, to make an otome game, to study otome games—especially queer otome games—these are all rebellious acts. It champions a genre and audience often dismissed as frivolous, when they’re anything but.

So, now that you know the basics, the next time you’re on Steam, itch.io, in your local game store, or even looking around online, consider giving an otome game a try. You just might also find yourself sucked into the stories—whether they’re about princes, pigeons, or beyond.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.