Content warning: Discussion of racism and microaggressions

Who doesn’t like cats? You can’t be anti-cat, you just can’t. And yet, when you sit down with the idea of self-aware humanoid cat people, you do not think about their wellbeing. You think about how we might “exploit their inherent cuteness” rather than asking the real question: what do cats need to gain equality to humans?

Hi, it’s me, Chiaki, once again thinking too hard about cats in media. Today I’m here to tell you that Aoka’s Neo Cat conveys how being celebrated doesn’t necessarily exempt you from racism. Fame and worship is conditional, so long as the dominant culture deems you safe and marketable, but true liberation and equality is unattainable so long as racist systems stay in place. Compared to an erotic visual novel about screwing your socially disadvantaged catgirls who waitress at your cake shop, Neo Cat dares to offer a humorous story about an advanced species of human-like cats that simultaneously are as cute as they are complex.

At first glance, Neo Cat seems like a surreal sight gag. Aoka’s elegant human character designs run counter to the cartoony cats depicted in the stories, creating a visual contrast that pulls you in with comedy. The comic has the gall to start on an in-your-face panel showing a small cat driving a full-sized Chevy Camaro, a gruff-looking grandpa at his side, and reading the story to understand what is actually going on reveals very little. A lonely old man gets paired with a cat on a platonic friend matching app and they bond over their love of the 1988 Luc Besson film Le Grand Bleu. The man teaches the cat to surf and paint and enjoys his companionship.

The story continues from there with seemingly non-sequitur short stories about different cats and their interactions with humans. A cabaret hostess wants to stan her favorite cat at a cat cabaret; a good looking man is scouted to walk a fashion show runway with cats; a kitten in preschool does his best to put on a play with his classmates; and a high school cat borrows an otome visual novel from her best friend. All of these situations feel familiar, even pedestrian in setting, but the cats add an element of strange to each chapter.

The fashion model wears a coat of living cats. The otome heroine – being a cat – makes quick work solving all the routes by putting on her catty charm. The cat cabaret juxtaposes Dom Perignon with cat food as the guests play with their feline hosts and hostesses. Neo Cat plays up what makes a cat a cat to sell their appeal while also being human-like in demeanor.

Just as Nekopara’s world operates on a cat-driven economy that sells the fact that “cats are cute” and that their likeness are meant to be commercially exploited, Aoka presents a world where humans knowingly exploit cats for their innate cuteness while overlooking their humanity. Yet, unlike Nekopara, Neo Cat consciously offers an opportunity for cats to self-reflect upon their exploitation.

The utopic assumption that intelligent cats in a human society would thrive is dashed for the reader in the third chapter when Aoka reveals there is more than meets the eye to the cats in Neo Cat.

“Chapalu” starts as the first two chapters did, with lighthearted surrealism. A calico cat wearing a t-shirt that cutely reads “Corporate Governance” meets with a magazine reporter doing a story on his cosmetics company. The cat, Richard Parker, leads Mao, the reporter, through his company, which employs many other cats working very normal office jobs. Save for their products taking on distinctly cat-themed motifs and the higher prevalence of cats in the office, Mao notes everything seems relatively normal.

Before finishing her tour, however, Mao observes a company mandated “cat nap” for all the cat employees in the afternoon. The journalist takes a moment to go on Twitter to say, “At Chapalu, the cat employees take an hour nap every day. Jealous!”

Yet the story takes on a serious tone the moment Mao begins her formal post-nap interview with Richard. Through the interview, the young reporter is humbled to realize what life is like for cats. Richard reveals he is not just a cute cat with good business acumen but a ferocious tiger fighting for civil rights. He explains that, while cats have gained equal rights to humans on paper, living in a human-run world leads to both active and passive discrimination of cats.

Parker reveals cats have faced considerable housing discrimination, and that humans lack an understanding of what needs they must address for cats to properly integrate into society. He explains the cute cat nap Mao gleefully tweeted about was designed to address the physiological needs of cats to sleep more than humans. Richard explains humans who ignored the accommodations needed by cats have created hostile work environments that have driven otherwise hardworking cats out of the job through burnout or on-the-job accidents.

He poignantly states: “I said this company is ‘for humans and cats alike.’ But while I may be the ‘president,’ I am also a cat who believes he must fight for all cats as well.” He reveals his desire to create a model for an inclusive society by using his company as a testing ground for needed reforms.

Most of the chapter-long stories don’t really examine the divide between humans and cats in this way, but Richard’s chapter serves as an explicit moment of clarity that fundamentally shifts how the readers should see the cats.

The playful fashion show segment using live cats worn by the model becomes far more sinister with the underlying realization that cats are second class citizens, even as the embattled fashion designer claims the cats are all paid actors who agreed to “perform” as the model’s clothes for the evening. The cats themselves seem unperturbed by the gig, happy to take the money and go party at a casino after the show while the press hammers the designer down with questions on the ethics of his stunt.

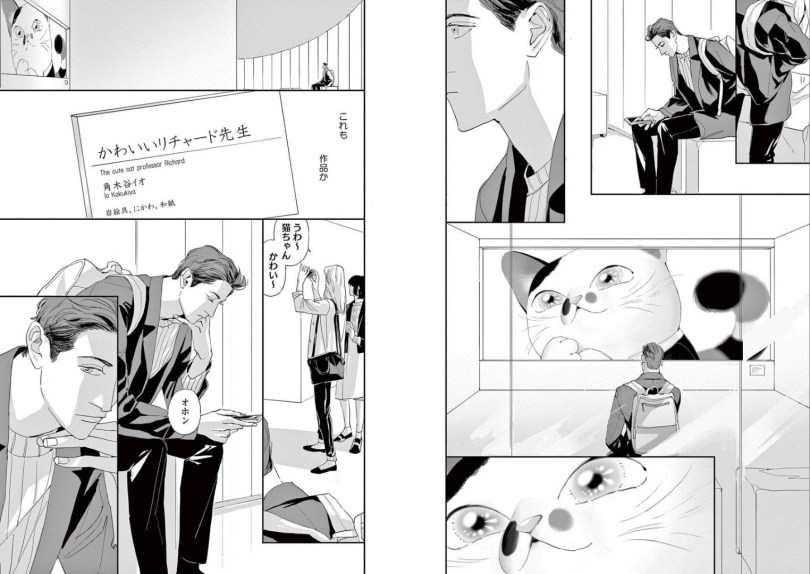

At the museum, Leonardo Peck, a tourist, meets Kenji Madelai, a tuxedo cat. The two look at a portrait of Richard to discuss whether the cat, as the painting’s name implies, is truly cute. Even here, the average human observer, unaware of Richard’s role in civil rights, simply looks at the painting and muses “wow, a cute kitty!”

The two discuss why Richard is portrayed so cutely. Kenji believes it’s a conscious effort to draw out how so much of Richard’s life has been trivialized by the four letter word. Leo counters that the painting can only be described as “cute,” but in doing so the positivity makes one question what hardships were omitted from the canvas. Leo feels the word “cute” by itself holds no negative connotation, but Kenji warns him that specific mentality and obliviousness to its loaded meaning to cats is what humans must learn to become aware.

Cats in Neo Cat are not merely downtrodden minorities. They face hardships, but Aoka places them on a pedestal, mostly through the concept of cats being “cute.” This appreciation, as Kenji warns, must be fully understood in all of its dimensions to enable humans to understand that merely praising them does not necessarily mean they’ve granted acceptance or mutual understanding. This undercurrent broaches the concept of the model minority myth.

This introspection hits home for Asian Americans who have long been held as “the good minority” in America. White culture would put Asians on a pedestal to prove a “lack of racism,” the idea being they can’t be racist if they are elevating another race for being smart and successful in a capitalist society. At the same time, by showing there are “good minorities,” the concept grants an oppressor the opportunity to criticize other races as “lazy” if they cannot find success in society. This scapegoating not only excuses racism, but drives a wedge between the so-called successful minorities and other races.

While Neo Cat does not present a third underclass to disparage or stand counter to the cats, Richard’s revelation on the state of the world touches on a second fundamental aspect of the model minority myth: their acceptance is wholly conditional.

As Asians can be seen as “the good minority” only as long as they are ultimately servile to whites, that modicum of privilege granted to them evaporates whenever convenient. Whether it’s to bear the downturn of the American automobile industry, to address fears of losing a global edge to science and technology, or to blame a disastrous response to an international disaster, the privilege afforded to Asians can dry up the instant the dominant white culture sense their supremacy is endangered.

In Neo Cat’s case, even as the hegemonic society supposes humans and cats are equal, the truth is far from it. They may thrive as hosts and hostesses in Ginza or as aesthetic in a fashion show – they may even become pilots for an international airline – but they are not afforded the right to the equity they need to thrive in a society run by humans.

Richard, himself, muses at this concept at the end of his story. He admits he had relied on the commercial viability of cats to sell his products, which has led to his success at capitalism, but he wonders if he truly is doing any good.

He wistfully decides to bide his time for a better future as he glibly states: “The reality is, humans hold all the capital. I will likely never escape having to pander to them.”

Ultimately, “Neo Cat” is about how cats are just weird little guys, but dares to go a step further to speculate the concept of being adored but powerless in society. And Aoka appears to be cognizant that substituting real life racism with fantasy racism can be trivializing.

The author notes in the afterward: “As I drew this comic I came to realize I’m surrounded by invisible glass walls, and I have had to reevaluate a lot of how I think and my sense of responsibility for creating something for a wider audience. I am a sunfish who managed to not break out of its aquarium, but if I have hurt another sunfish out there by doing this, I offer my deepest apologies.”

Aoka seems aware that Neo Cat is risking trivialization by trying to address racism with a fictional class of oppressed people, but that awareness more importantly breathes life into a world. It is a fictional world that feels alive and is willing to tackle itself in all of its complexity. Whereas other properties will simply ask the reader to “(d)on’t think too much, just adore cats,” Aoka dares to ask readers to think a little harder in order to bring life to a world with messy cats.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.