Content Warning for child abuse, medical neglect, and ableism

Spoilers for all of Sailor Moon S.

“Pain is different when you’re a lifetime achiever at it”

—Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

I first met Hotaru in my last year of college. After a week hunched over an unfinished thesis and having migraines every day, I would watch Sailor Moon S for comfort, and Hotaru was who I looked forward to seeing most.

I saw Hotaru try to leave her prison of a home, and every time, it seemed to me she was punished by her body. First she would suffer severe pain, and then seizures would knock her unconscious. At the time, I viewed myself as at war with my body, a war that had lasted since I was a child and a war I was constantly losing. I would come home every day and lie in bed in extreme pain from migraines, socially isolated because my unhealthy coping mechanisms for the pain would drive friends away. So seeing Hotaru begin to thrive, making friends and leaving her house, gave me hope that I would too be able to overcome my disability.

This hope made her fate all the more shocking. Here was a character who I was ready to see break out of her suffering coming the closest of any Sailor Moon character to actually dying. This ending for her made me go back and rethink much of how Usagi and Chibiusa treated her–were they the friends Hotaru needed? Or just another savior misunderstanding her needs?

As I’ve revisited Sailor Moon after having been diagnosed with severe, disabling chronic migraine, come to terms with my Autism diagnosis, and spent time in disability justice spaces, I’ve found Hotaru’s representation to be far more nuanced than I remembered it. Hotaru’s story represents the tension between our desire for comforting narratives of disabled people healing and the reality of disabled life as shaped by capitalism and the limits of our bodies.

Overcoming Disability Narratives

Over and over again in Hotaru’s story we see the influence of what might be called an “overcoming disability” narrative. Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, a disability theorist and organizer, defines overcoming disability narratives in her book Care Work as being “the only disability story they [publishers] can comprehend–a single, tragic yet uplifting tale where I talk about my ‘illness’ and how I have ‘overcome’ it.”

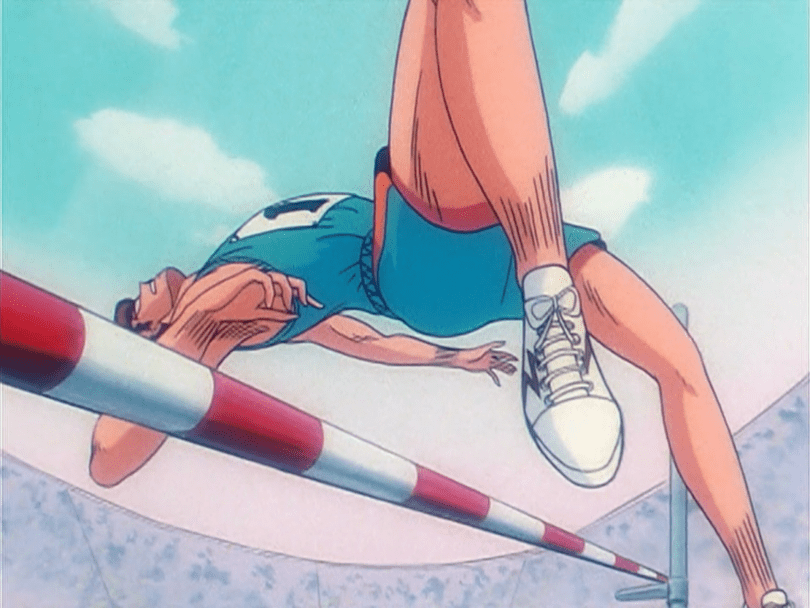

Sailor Moon S has a straightforward overcoming disability narrative in Hayase, a track star who was very sick as a child but eventually recovered to become a world class track star. In a very funny, Ikuhara-esque episode, Hotaru tries to get in contact with him because she sees in him a possible future for herself getting over her illness. In the moving ending of the episode, he tells her to get better so she can be like him.

Overcoming disability narratives are a complicated ethical tangle because they present disability as something that we should be cured of, as the narrative resolution becomes the cure for the ailment. These narratives’ being the only stories of disability we get both reflects and reinforces the larger goals of society when confronting disability, which is not “how do we support and make space for disabled people,” but “how do we get as many disabled people to stop being disabled as soon as possible.” Any disabled person whose disability cannot be cured is viewed as a tragedy, someone cut off from their true potential, something to be pitied. The responsibility for that person’s exclusion from society is placed not on society disposing of them but on the disabled body itself.

The desire for a cure for disability is also in itself fraught. On one hand, I’m sure both Hotaru and I would very much like to be rid of our chronic pain! And, for these sorts of disabilities, it can give us both solace for the present and hope for the future to see representations of people who had been in situations similar to ours and made it out the other side.

By contrast, there are many disabilities which do not need a cure, but social acceptance instead. I do not want to be “cured” of my autism, as it makes me who I am, and I like who I am. The suffering I experience as an autistic derives almost entirely from the social exclusion that ableist society puts me through, rather than anything inherent to the condition itself. Similarly, one could describe Hotaru’s condition as she is possessed by Mistress 9 as a sort of Dissociative Identity Disorder, another “disorder” which is largely defined as such because of stigma rather than an inherent deficiency. Many people with this “disorder,” who self-describe as plural, do not want to be cured of their pluralness. To destroy their pluralness, or to destroy my autism, would be to destroy who we are–as indeed, Hotaru must die to be cured.

Hotaru’s Exclusion as Extractive Abandonment

It’s hard to talk about Hotaru’s death without talking about the ways that society made her monstrous, exploited and harmed her. Throughout history, many different laws and methods have been used to keep disabled and chronically ill people away from society, often in a position of exploitation. Whether through leper colonies, ugly laws, mental institutions, or many other forms of carceral ableism, disabled people are institutionally excluded and sometimes even imprisoned.

This exclusion is justified through repeated gestures at the alleged monstrousness of disabled people. Over and over again, the surrounding society bullies, gaslights, and generally treats Hotaru as less than human. Her father and Kaolinite manipulate her into staying in her room as much as possible, allegedly for her own good, purposefully isolating her and pushing away Usagi and Chibiusa. All the easier, of course, for them and the Witches Five to use her as a conduit for their experiments extracting people’s pure hearts.

Hotaru experiences a fantasy version of what Beatrice Adler-Bolton and Artie Vierkant call extractive abandonment–where disabled members of our society are kept in a state of slow death through systems of capital that serve to extract from them everything they can. From Hotaru, the pure hearts of children are extracted, to be used and thrown away, while she suffers enormously in the process. From the “surplus” of society, as Adler-Bolton and Vierkant describe disabled people too sick to work, all of the lost productivity must be recuperated in the form of profit for the medical industrial complex, which puts the surplus on an endless merry-go-round of prescription denials, dehumanizing nursing homes, and other ways to generate money from disabled people’s bare survival and scrounge money from their wallets. This extraction serves both capitalist and also geopolitical purposes, as shown in Jasbir Puar’s work on Israel’s mass disablement of Palestinians in the open air prison that is Gaza. If you render an entire population surplus, you can weave extractive abandonment into your imperialism.

Hotaru and disabled people’s living full and meaningful lives, regardless of whether a cure is in their future, is not in the interest of those who hoard power over us. Care, access, and support for all people, not just white rich people, is the door out of the cage where capitalism and imperialism traps and extracts from us. Capital will do all it can to bar our exit.

Usagi, Chibiusa and Access Intimacy Denied

Usagi and Chibiusa appear after Hotaru has largely internalized her state of slow death. Having experienced heaping piles of abuse from Kaolinite in addition to being locked away by society, Hotaru constantly has nightmares about hurting her classmates and friends, and constantly apologizes for her seizures. Despite this, Hotaru wants desperately to have friends, and when she encounters Chibiusa, she refuses to let Kaolinite cage her in anymore.

Chibiusa and Usagi in turn resist Hotaru’s disposability, supporting her in trying to escape from her home life. From the beginning, Chibiusa treats Hotaru largely as normal. She reaches out to become Hotaru’s friend just after Hotaru has a mild seizure in front of her, but not from a place of pity. And while much of the narrative arc of the show rests on whether it is justified to kill Hotaru to save the earth, as Sailor Uranus and Neptune believe, the show is firmly on Usagi and Chibiusa’s side in this. Even when Mistress 9 takes over Hotaru’s body, Usagi and Chibiusa fight to save her, believing that Hotaru is still in there somewhere. They seem to represent the creators’ view of disability–that disabled people deserve full, happy lives where they are treated as normal rather than anomalies.

Yet Usagi and Chibiusa’s interventions in Hotaru’s life sometimes come from a place of ignorance, reinforcing harmful narratives about disabled life. Disturbed by the grim, prison-like state of Hotaru’s existence in her house, they invite Hotaru out to meet with them outside. When Hotaru does escape from Kaolinite’s grasp to meet them, she has a severe attack of seizures and is hospitalized. As Chibiusa blames herself for Hotaru’s state, Usagi comforts her, telling her that Hotaru “forcing herself” to leave her house to the point of being hospitalized shows how much Hotaru loves them, and that it is now Chibiusa’s turn to show up for Hotaru in her time of need.

I’ve thought for years about her equation of forcing one’s self beyond the limits of one’s disability as showing love. I’ve thought about just how many times I worried that people would think that because I canceled plans due to a migraine, or had to ask for significant accommodations, that I didn’t care about them. I’ve realized it should not be on disabled people to “push ourselves” to show that we deserve friends. True friendship with and among disabled people involves what Mia Mingus calls access intimacy–the process through which we grow closer as we learn how to best meet each others’ needs and create accessibility in our friendships.

When one has internalized the violence of extractive abandonment like Hotaru has, it can be hard to voice one’s needs in the direct, explicit ways that are required to create access intimacy, especially when so often abled people throw away their disabled friends the minute their access needs become inconvenient. So instead, you repress your access needs, holding white-knuckled onto your friendships even at risk of your health. In some ways, Usagi is trying to show Chibiusa this aspect of Hotaru’s experience. She wants Chibiusa to see how hard Hotaru is working to be Chibiusa’s friend, encouraging Chibiusa to be there for Hotaru in a way that other people have not. The next scene reinforces this reading, showing all the ways Hotaru’s classmates abandoned her after one of her seizure episodes.

Despite her attempts to instill empathy in Chibiusa, I cannot not stop from hearing overtones of saviorism in Usagi’s words: that Chibiusa is there to be a stepping stone on Hotaru’s overcoming disability narrative. Chibiusa is there to lovingly invite Hotaru into an inaccessible world, not to fight to make the world accessible to Hotaru, nor is she there to build access intimacy with Hotaru. To complete this narrative arc, Hotaru will have to abandon her access needs.

This is the true harm of the hegemony of the overcoming disability narrative: the idea that your access needs are a mere hindrance that you should always be working to be rid of. In the real world, this manifests through treatments such as the clinical gaslighting that people are subjected to with MECFS (Myalgic encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome), graded exercise therapy. Studies consistently show this therapy, in which patients are encouraged to slowly ramp up their physical activity, actually harms the patients involved, yet, because of the ableism of the medical industrial complex, it is still standard practice. We must resist at all times the narrative that if disabled people would just push themselves more and abandon their needs, then they would get recover, and that this form of self-harm is how disabled people should show their love.

I Guess This is an Overcoming Disability Narrative

About a year ago, right around the time I first started working on this article, I started seeing a different neurologist. They prescribed me a new medication, and, for the first time I could remember, my daily migraines turned to weekly migraines. I started going to raves. I started being able to go outside without sunglasses. I started playing my saxophone again. In other words, I was living out the overcoming disability narrative I was so skeptical of.

For so long, I felt the terror of living on the edge of the surplus, constantly at risk of becoming too sick to work and experiencing extractive abandonment. That threat kept me working even as I was in pain every single day and kept me from taking medical leave when I needed it. It made me accept how every ounce of energy I had would be stolen by my work, and that I would never have a social life. That I am no longer in that position, that I am much farther away now from the knife’s edge, is comfort only in a selfish sense, given I know that other people fall off of it every day.

Hotaru was not as lucky as me. It is only her death/rebirth that purged her of her illness. I struggle often with this ending for her–to think that the only form of hope that the creators could think of for her would be her death and rebirth. When Usagi beats the ground, crying “Crisis Power, Makeup,” pleading with the narrative to allow her to save Hotaru, we can feel Sailor Moon pushing at the limits of the overcoming disability narrative, unable to make it coherent with what it knows about the reality of Hotaru’s illness.

Many of us have to live with our illnesses for the rest of their lives. We find our ways to cope with them, continuing to be extracted from and living out a slow death if we are unlucky enough to be rendered surplus. I want more for Hotaru than death, whether slow or rapid. Her narrative should not need to be a comforting one of overcoming for her to be able to find community, access intimacy, and be loved. It is only through confronting the negative, through confronting the limits of our ability to overcome these disabilities, that we can know one another.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.