Monsters have always had a place in society, serving as omens of the darkest parts of human nature. They were a warning; an ominous presence reminding us of our own humanity.

As a gloomy girl growing up in the middle of nowhere, I loved monsters. Instead of something to be scared of, their presence alluded to there being something out there far grander than everyday life. And it was the monstrous women that I was drawn to, proving themselves as pillars of strength rather than terror: Medusa, fighting back against sexual assault; Lilith refusing to kneel.

But as I grew older, it quickly became apparent that these monstrous women served as more than just a warning. They were a reminder, directing your attention to the “other” that resided just on the outskirts of what a contemporary society aspired to look like.

Even so, when I began to watch anime, I gravitated towards shows that featured women as more than just static characters. I sought out the messy, chaotic, subdued, and the grotesque—anything that showed girls being something other than well-behaved or stereotypically “girly.” And where I sought out women that were extraordinary, it was the monster girls that truly caught my eye. Despite being relegated to objectification, these monstrous women and girls have the ability to become representatives of women who not only deviate from the norm, but stand out.

No strangers to anime, monster girls have been featured in numerous shows over the past few decades, such as Petopeto-san, Hyper Police, and Devilman. These shows have been all over the map, ranging from ecchi harem to slice-of-life. But classic monster girls have looked overwhelmingly human. Sure, they might have been monsters, but they looked just like anyone else, minus maybe a furry tail or cute cat ears.

Recently, however, the girls began to change and take on new appearances. More and more shows are featuring women that are closer to monster than human with fins, gills, fangs, and claws.

As character designs for these monster girls become more amplified, their objectification through fanservice does as well. Due to this fascination with monster girls’ bodies, most of these shows rely heavily on fanservice. While fanservice isn’t inherently a problem, the issue lies in the way the series used monster girls to provide it.

In shows that prioritize fanservice over story, characters are often made to suffer. In moments of physical vulnerability, the camera pans and lingers over exposed bodies. With monster girls, the suffering seems amplified, as their bodies are further objectified for their alien appearance. They are simply there to titillate; to engage with the audience in a sexual way. Instead of bodily autonomy, the monster girls’ physical bodies are tied to the story rather than to the girls themselves. It’s almost as if the body is a separate character in the story.

One example of fanservice colliding with monster girls occurs in the anime adaptation of Monster Musume. The show was a surprise favorite of mine, telling the story of an average man named Kimihito Kurusu trying to live a normal life until a lineup of monstrous women fall in love with him. After the government sponsors an interspecies exchange program, Kurusu ends up being the host for multiple women of different species, ranging from a lamia to a dullahan.

Monster Musume is incredibly transparent in what it is: a raunchy comedy with more than enough fanservice to make even a seasoned anime veteran blush. However, it’s also incredibly aware in how it presents the characters within it. Because of this forwardness, it also treats its characters pretty fairly a large part of the time.

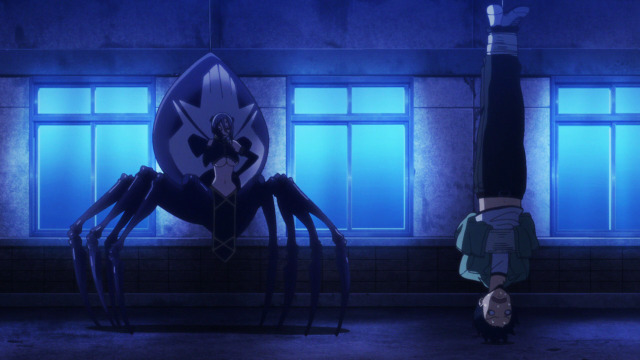

One character who exemplifies Monster Musume’s storytelling style is Rachnera the Arachne, a spider-human hybrid of sorts. She’s powerful, fast, and incredibly unapologetic. The show plays up her arachnid tendencies in sexual ways, such as her web-spinning as a form of BDSM.

In many modern monster girl stories, the monster girl’s body is often tied to their character or serves as a point of focus on-screen. Despite visually serving as a source of fanservice, Rachnera’s body also helps tell a story about what is truly monstrous for her and how she finds power within her own body because of how it looks, not in spite of it.

In one of their first interactions with each other, Kurusu compliments Rachnera’s legs. She reacts as if he’s insulted her, because she thinks he’s only attracted to her human half—not her arachnid bottom. However, Kurusu reaffirms he truly says so from a place of admiration. This sparks the beginning of Rachnera navigating body positivity.

It’s not always easy for her, and as viewers we experience her moments of discomfort, shame, and enlightenment. Rachnera blurs the line between what’s monstrous and what isn’t, but not in ways we would expect. She comes off as sadistic, intimidating, and even cruel at times. But as the show continues, it comes to light that she has a troubled past filled with abuse, neglect, and even trafficking. Part of her woes stem from the fact that she looked more monster than human. For Rachnera, what was truly monstrous was how others reacted to her body and not to her as a person.

While I love to sing Monster Musume’s praises, it’s not without fault. Throughout the show, most of the moments of fanservice are initiated by the girls themselves. They try to present themselves as potential mates for their host and we watch as they stumble through attempts at seduction. But occasionally, that fanservice falls out of their hands and into those around them. The fanservice then feels incredibly voyeuristic.

One such episode is when Kasegi, a con artist, works his way into Kurusu’s household under the guise of filming a documentary. Throughout the episode, he catches the girls in compromising positions, from slipping on bikinis to actual groping. It’s uncomfortable to watch, particularly with Papi, the harpy, who is about to lay an unfertilized egg. It’s a difficult episode to sit through, especially when prior episodes hadn’t derived lust-filled moments from monster girls suffering at the hands of a pervy con-man.

While Rachnera and Papi in Monster Musume sit at the more extreme ends of the spectrum in terms of isolation and objectification, they’re not alone. More humanoid monster girls also face similar issues of ostracization by being considered “other.”

Interviews with Monster Girls presents monster girls who are grappling with their bodies and contemporary society. Similar to Monster Musume, monsters exist and mingle in society as “demi-humans”; however, the cast of Interviews aren’t competing for the attention of a love interest, but instead are people simply wanting to live their lives.

Though the series recognizes the demi-humans’ humanity, they are not wholly separate from their monster identities. Interactions between demi-humans and humans in both Monster Musume and Interviews always tie back to the girls’ bodies. However, the two series frame these interactions very differently.

In certain cases with Monster Musume, we are supposed to not only empathize, but also lust after Rachnera. On the other hand, in Interviews with Monster Girls, we’re primarily observant to the girls’ growth. Because of the compassion that seeps through the writing, we’re never supposed to mock the demi-humans, be scared of them, or leer at them. Instead, we’re meant to empathize and even grow with them.

For example, Sakie Sato, one of the teachers at the school where Interviews takes place, is a succubus. It would be easy to allow her character to become the joke of the show, using her status as a succubus to introduce fanservice. Instead, we see her struggling to keep her abilities from impacting those around her, particularly those she cares about. She lives far from people, takes early and late trains to avoid contact, and wears modest clothing. Sato genuinely wants the people around her to be safe from her. And we, as viewers, are aware that she is not inherently dangerous. It’s easy to sympathize with her.

Interviews is a refreshing change of pace from bawdy harem-style shows like Monster Musume, where the heroines’ bodies are the primary focus for both the show and its protagonist. Writing can always make or break a show, but with monster girl series, the writing is what takes them from being a spectacle to being characters in their own right. Both shows have shining examples of stellar writing that elevates the girls into people instead of just fetishes, but Interviews with Monster Girls presents a more well-rounded cast while Monster Musume, at the end of the day, focuses on fanservice.

Of the demi-girls in Interviews, the dullahan Machi sticks out from her classmates in an incredibly noticeable way: her head isn’t attached to her body. And though it is used in certain situations to elicit a reaction, the show does not objectify her through her unique body. Instead, it’s used to elicit empathy. In writing her in a way that doesn’t use her body for shock value, she instead becomes a metaphor for body positivity or even disability rights.

As Zeldaru pointed out in their poignant article about Machi, when Machi meets the physics professor Souma, he crouches to meet Machi’s gaze and make eye contact. It’s a subtle but powerful moment that highlights the importance of inclusivity and the show’s acceptance of Machi’s body.

It’s also a fragile moment that might have fallen apart with subpar writing. The scene could have been a gag joke or an awkward misstep in conduct. Instead, we get a touching moment improved by one character accommodating another’s physical needs.

Machi and Rachnera both show that one’s appearance can be a source of loneliness, but also power. Both find reprieve in their bodily autonomy, growing within themselves and evolving in their mindsets. Their bodies are not inherently monstrous, but as monster girls they are constantly reminded of the fact that they are different from the humans around them.

As long as monster girls appear in pop culture, discussions about them will focus on their bodies. But they can escape the lens of objectification through thoughtful character writing. Monster girls have gone through everything we’ve thrown at them: from the horrors of high school to social integration programs. We at least owe them a good storyline.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.