CONTENT WARNING for discussion of racial stereotyping and sexism.

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to work on the first full U.S. release of one of my favorite franchises ever: Mazinger Z. The 1972 super robot show rewrote the rulebook for giant robots in anime and launched decades of remakes and reimaginings. It’s safe to say that, without this Go Nagai classic, the landscape of anime (and much of genre entertainment) as we know it would be very different. And I loved every cheesy minute of it. Yes, even the evil Santa robot with the missile-firing whip.

But when you’re putting one of your faves under the microscope in a business context, new things suddenly jump out at you. With only remakes and video game appearances to work from, I was largely unaware of the show’s roots. And while I was all-in for the cheesiness and monster-of-the-week action, I was caught on the back foot when it came to certain elements of the show.

Sayaka, for instance—protagonist Koji’s battle partner and love interest, whose father deliberately gives her an under-equipped robot to discourage her from going into battle. The way she’s talked to and about throughout the series, and the scenarios she finds herself in—being told to be a “good girl” in various situations, having Koji’s younger brother call her “undesirable” based on her temper, and being depicted as catty (nails and all) in her fights with Koji—were vastly different from the robot pilot heroine I’d come to love. But those differences were there on the screen, indelible for four decades.

Or some of the mechanical beasts, such as a robot inspired by North American indigenous peoples that evoked “comic” dialogue that wouldn’t fly today (Boss fleeing in terror yelling “I don’t want to get scalped!” amongst it). But there it was. The dialogue was being said by one of the pilots.

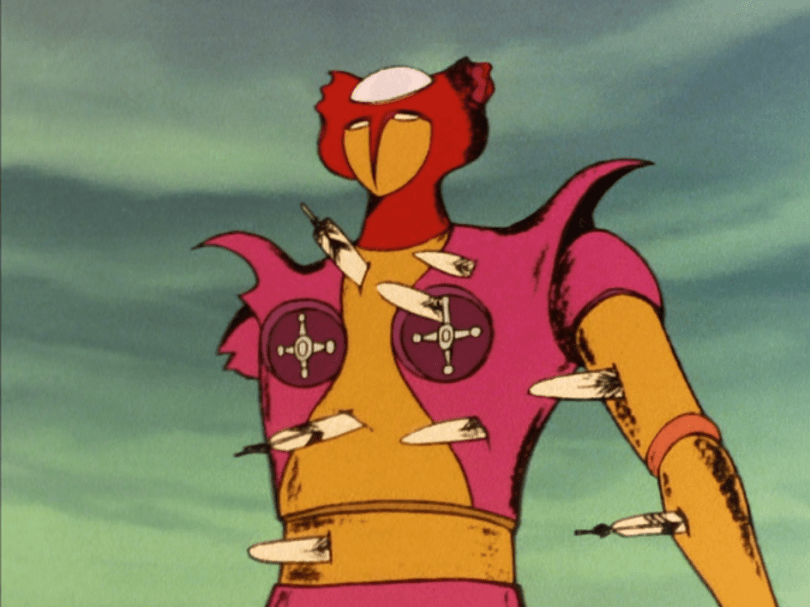

And then there was the doubly indelible Viscount Pygman: a rad lion-riding dude in the 2005 remake, here literally an African racial stereotype stacked on top of another racial stereotype. The localization staff quickly understood why his six episodes were cut from TranZor Z.

I loved Mazinger Z. I still do. But these extra discoveries were awkward, like a family member who’s good in public most of the time but will start talking politics when you least expect it. And the desire to tweak, temper, or even completely alter some of those lines was huge.

At the same time, this release was described a very specific way: it would be the first time ever that the original series was released in America unedited. Save for a handful of lines that were up for interpretation, my job was clear: bite down on my left hand and edit with my right.

There was never even a discussion on what we “ought” to do in these cases; just some knowing looks, a few sighs, and getting it over with. After all, this was Mazinger Z: The good, the bad, and the ugly. The unedited. Even if that meant a handful of moments that we aren’t particularly fond of.

That said, just because we didn’t need to consult with each other about it doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be consultation. As we speak, companies I’ve worked with are asking employees to alert their localization team to any occurrences of the slur “trap” in back catalog entries so they can be removed and replaced. In these cases, the issue isn’t with what the original Japanese script says—it’s with the localization team’s unwelcome terminology.

There are a variety of cases where you’ll find yourself with unwelcome terminology or dialogue in a localization, and each warrants its own consideration and context. If anything, handling cases of unwelcome or distasteful terminology ought to be (at least for certain shows) a part of the localization process in the editing stage

The first case we’ve already discussed: the “product of its time” scenario. When working with older series, it doesn’t fall to us to change the language, because while that does remove the instance of it (in the subtitles) for this particular release, it does not erase the utterance from history. It’s a flimsy bit of white-out tape over something quite real.

It should be left, not out of “respect” for the original material or “acknowledgment” of a different set of standards, but because falsely erasing a real happening does more harm than good. (Note that if this is a dub to be shown on television, there’s a whole other set of rules at play, and decency measures will need to be considered.)

Occurrences of this in modern anime as a whole, prior to localization, are a bit more diversified. We’re usually dealing with works by a creator who’s still alive—who, perhaps, may even still be creating the anime or its source material as we speak. This isn’t a matter of the creator coming from a different time and different ways of thinking. This creator will hear about today’s episode tomorrow. And so will the localization team.

So what accounts for these more diverse considerations? One simple point, which must always be asked when confronting a slur in localized dialogue:

Who is using the word: the writer, the character, or the localization team?

At a glance, it may look like all those things amount to the same thing, but we’re looking at the source of the phrase. Break it down like this:

- A specific character whose nature is to say offensive things may have said it, solely within the context of the piece, as written by a creator who’s depicting the character but not agreeing with them.

- A creator may write characters speaking this way in general, betraying a personal bias.

- The word used may be benign in the original language, but someone on the localization team—either because of personal bias or inadequate vocabulary—has plugged in a slur instead.

At this point, you might expect me to give you a step-by-step guide for how to handle each of these issues, and what’s the “right” resort in every case. But I can’t. Or rather, I won’t. Because that would assume that every instance in each heading would always have the same answer, applying to every team and every viewing demographic. And that’s not the case.

The answer is more that we, as professionals in the anime industry, need to make sure we’re having these talks in the first place. And, more importantly, we shouldn’t fear these talks. If our job is to present our audiences with the most understandable and accessible product, then we need to take care how we handle translation decisions that could completely change how the audience receives the product.

The fact that many licensing companies are doubling back to address previous issues is a good start. But we need to address them in the moment, before the product goes out, as often as possible.

Do shows like Mazinger Z warrant a disclaimer up-front as Warner Bros. does for many of its Looney Tunes releases? Possibly. Again, it’s a talk to have.

What do we do about shows where the offensive terminology is so deeply rooted in the material that there’s literally no way to localize it without keeping those elements intact, but we’re under contract to release it? Once again: a talk to have. Potentially on a bigger scale.

There is no one-size-fits-all answer for the problem, and acknowledging that is the first step to finding answers in each situation. This also means acknowledging that unpleasant terminology isn’t always completely damning for a show. Rather, it’s a matter of how the team chooses to deal with it.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.