Content Warning: Discussion of misogyny, anti-LGBTQIA messaging, and harassment

Spoilers for Death Note

Releasing just as scene kids came into their own, digital spaces became readily available to most American teens, and anime had finally carved out a small niche in mainstream culture, Death Note was destined to be a cultural phenomenon. In the years following the anime’s 2006 premiere, you couldn’t go to a convention without seeing clusters of Light, Misa, and L cosplayers. You couldn’t even spend fifteen minutes scrolling through an anime forum without finding L and Light avatars roleplaying an off-topic sleuthing session—much to the moderators’ chagrin. To this day Death Note remains a pop culture staple, with Grimes’ recent single even paying homage to the series.

Hailed at the time as a gothic detective thriller with themes that cut to the bone of modern society’s hypocrisies, many young anime fans thought that this would be the serious, daring work that would earn anime the respect and appreciation the medium deserved. As I rewatched the series in 2022, though, I can say without a shadow of a doubt that we were wrong. Oh boy, were we wrong. Death Note is camp.

This isn’t to dismiss the intellectual value of Death Note or the personal impact it had on its fans; in fact, new layers and new ways to appreciate the series emerge when it’s considered as a campy melodrama rather than the brooding thriller that writer Ohba Tsugumi intended it to be. Before we analyze Death Note from the perspective granted by the passage of time, we first need to define the intentionally vague genre of camp. Then we can get into what this series is saying when examined through a camp tinted lens, and what Death Note being camp reveals about the changing anime fan community.

Camp is an intentionally nebulous style and genre that’s generally denoted by an exaggerated flare and sexual edge. As noted in Susan Sontag’s widely cited Notes on “Camp” essay, “The essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” While this is definitely a great starting point on understanding camp, the trend is a lot different today than when Sontag wrote her essay in 1964; and even then she undercut how much of a role the Black queer community played in establishing the aesthetic.

As explored by Taylor Crumpton, “camp in the United States was spearheaded by our Black queer ancestors.” Much of the visual presentation associated with camp in 2022 comes from Black queer communities using different artistic mediums, most notably drag, to make statements on heavy subjects like gender expression, class inequality, and racial discrimination. The deliberately absurd extravagance of camp media was used as a means to defang these incredibly serious subjects and allow for a more nuanced and comfortable exploration of them.

This genre and its evolution should matter to members of the anime fandom, since some of the most impactful anime and manga are peak camp. Araki Hirohiko’s JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure is decidedly camp and uses its voguing, mostly male cast to undercut socialized expectations of masculine sexuality. Studio TRIGGER’s Kill la Kill also uses camp sensibilities to explore divisive tropes in shonen action anime, like how women in “bikini armor” are both sexually objectified but potentionally inspirational when written with enough agency. Then there’s the original FLCL, which is joyously extra and also a deep rumination on the loss of childhood innocence, unrequited love, and the formation of identity. Even the first season of Attack on Titan has camp elements; from the characters’ singular but potent motivations to the nearly over-stylized action, the early seasons in particular are dialed up to eleven.

Now, you’d be right to point out that all of those examples of camp in anime and manga have decidedly different art styles, settings, themes, and plot structures. But we can look back to the elements of absurdity, exaggeration (whether intentional or not), and high levels of dramatic aesthetic, when looking for what we might define as “camp.” One of the single best examples in shonen is a series that preceded Death Note in the pages of Shonen Jump by only a few years: Yu-Gi-Oh!.

The series best known for spawning a worldwide trading card franchise began life as a horror manga during its early run, and it keeps elements of that darkness throughout the series. The origin of the central plot items is tied to ritual genocide and multiple characters have backstories involving graphic parental abuse, but these high stakes are fought through the medium of, to quote the meme, “a children’s card game.” That combination of weighty subject matter and petty, commercialized framing, plus characters facing off homoerotically while wearing dramatic winged eyeliner and outfits bedecked in leather and chains, is the perfect recipe for camp. Based on this working scope of what camp is, we can now analyze Death Note.

One of the best things about camp media is that the author didn’t have to intend for a work to be camp for it to fall into the genre. Ohba clearly wanted this work to be an examination of morality, the nature of justice, and the great man theory; but fumbles when it comes to writing about actual social issues. Look no further than his fundamental misunderstanding of LGBTQIA discrimination to realize that Ohba’s musings on society aren’t that well thought out. It’s ironies like this that make reading his various works as camp a sort of reclaimatory act, alongside an analytical one.

There’s a lot to glean from Death Note if you view it not as the author intended, but as a campy work with exaggerated characters and situations. Aspects like Light’s characterization as a boy genius power fantasy loop around to render him a pantomime of himself. He and L are meant to be the smartest men alive, and yet their arguments on morality are paper thin to adult eyes because they’re limited by Ohba’s stilted writing. The common trope of a shonen protagonist furtively ogling porn translates into Light staring listlessly at centerfolds in order to mask his actual murderous hobbies.

The series goes out of its way constantly to point out what a brilliant and attractive young man Light is, while juxtaposing this with private moments that show Light’s interiority. Under his facade, he’s an egomaniac who cackles in delight as he proves he’s the smartest person in the room and eats potato chips as though he were delivering an eleventh commandment. The voice acting, framing, and visual effects turn every minor thought or action into an operatic cataclysm; and Light is written as such an exaggerated portrait of the cool, straight ubermensch that he ends up comical and ridiculous, providing fuel to mock this character type rather than embodying it unironically.

Light is a study in irony: Light needs the constant praise from those around him to validate his behavior, yet he insists that he’s above the opinions of his peers. He is also outright disparaging to women whose admiration turns to romance. From his interactions with Misa, it’s clear that he cares more about women being interested in him and the status that brings than actually forming relationships. His hypercompetence and his distaste for women combine, amusingly, to make Light’s most meaningful relationships those with male rivals such as ace detective L, imbuing what are probably meant to be intellectual bouts with overtones of longing and sexual tension.

You’d be forgiven if you mistook the plot point where Light and L are literally handcuffed together while Light has homicide absolving amnesia as saucy slash fiction instead of a real story arc. The history of homoeroticism in shonen rivalry is long established, and there is no heterosexual explanation for this scene, where L tenderly dries Light’s feet as he laments how circumstance will soon pull them apart. It’s almost heartbreaking to see these two characters lack the facilities to express or even process their attraction to one another, and with this at its heart the series can be reconfigured as a sort of high drama romantic tragedy.

Speaking of Misa, Death Note is also misogynistic to the point of near parody. Yes, the manic pixie dream girl who helped keep Spencer’s in business in the late aughts is a collection of misogynistic tropes, but the whole series is bad to women. Death Note seems to believe that women are inherently a hindrance to a given situation or an obstacle to overcome. Whether it’s Misa’s mere presence being an annoyance to Light or Misora Naomi being a brief thorn in his side, women only seem to get in the way of the astute men in Death Note. This series so fundamentally misunderstands women and how they interact with the world and each other—like Misa and Takada fighting over Light after he was a terrible boyfriend to both of them—that it’s hilarious in retrospect that anyone took any kind of social insight from this work! It’s frighteningly clear that the only people who could connect with someone like Light and value his ideology are self-important weirdos, and in that grim hilarity is camp.

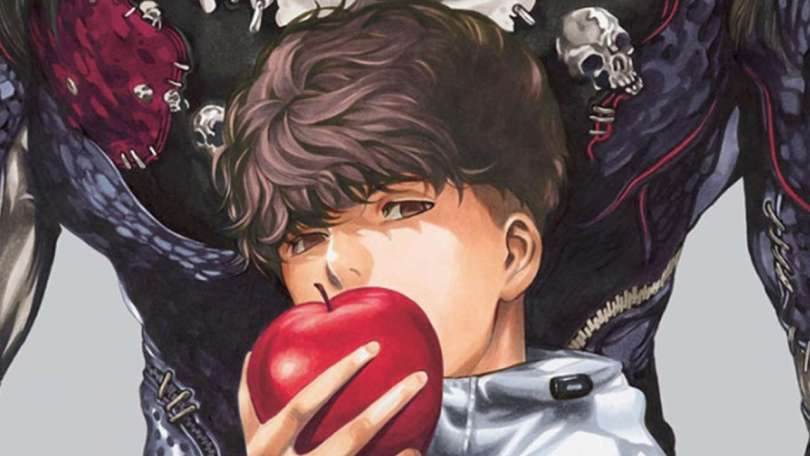

No evaluation of Death Note would be complete without mentioning Ryuk, the death god whose weird devil-angel aesthetic drips with theatrical gothic appeal, and who giggles through the events of the story. Perhaps intended to gesture towards the futile nature of Light’s ambitions, the shinigami feels more like an audience surrogate who’s as entertained by the story as we viewers are. Ryuk effectively winking to the crowd and making you want to laugh with him is what first tipped me off to Death Note making more sense as a work of camp fiction. Ryuk is genuinely the most relatable character in this work, and the biggest argument for reading Death Note as an absurd spectacle.

As the anime community has grown older, more and more people have warmed to this reading of Death Note, and that’s heartwarming in a couple of ways. For one thing, it’s great to realize that a piece of media I obsessed over as a teenager does have deeper meaning, even if it’s unintentional.

The second is that Death Note being reclaimed as camp spites the unsavory folks who first latched onto it. Gatekeepers and edgelords made Death Note their own when it first became popular and used their affinity for it as an excuse to harass people. Those forum users with Light avatars would absolutely make in-character and thinly veiled death threats to people who had a different opinion on an anime they liked, or even if you hated an anime for a different reason than they did.

Through a camp lens, though, Death Note can be celebrated as messy, sexually charged pulp detective fiction. Being able to engage with Death Note as a queer, campy piece of media is a testiment to how different today’s anime fandom is to the community from fifteen years ago. Sure, there were people pointing out how ridiculous and queer-coded Death Note was back when it first released, but the community would generally shout them down or write them off as LawLight shippers. Now there are numerous people viewing Death Note as a wild piece of camp art in prominent spaces and it’s commendable how much more widespread and inclusive the anime fandom is today.

Or, maybe it’s me that’s changed. When I watched Death Note as a teenager I definitely hadn’t lived enough to recognize it as camp; nor did I have as firm of an understanding of my own sexuality as I do today. I took it super seriously and thought I’d be returning to a problematic fave, but was delighted to realize that Death Note is camp. Accidental, ostentatious camp that, in its attempts to create a dark and edgy power fantasy, stumbles so spectacularly that it tears down some of the worst kinds of people and beliefs around today.

That’s what I love about camp, and what I now love about Death Note. I don’t have many solutions to problems like misogyny coloring all aspects of society or Light wannabes being rewarded for their behavior, and can think of few media that posit their own answers. Camp doesn’t have to present solutions to these problems, though, and can instead just mock them. Death Note is weird, fun, gay, and it’s invigorating that I can return to a piece of media and gain a whole new appreciation for it as a work of camp that likely influenced me in ways I never realized.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.