Spoilers for Kaze to Ki no Uta

Editor’s Note: Works that do not exist in English are written [Japanese name] (English translation), and works that do exist in English are [English translation] (Original Japanese). English titles follow English capitalisations (eg. The Heart of Thomas), and Japanese titles follow Japanese capitalisations (eg. Touma no shinzou).

Amongst the manga authors who rose to fame in the last century, Takemiya Keiko is one that most people don’t know—or so they think. It is not for any of her faults, of course, but for her link to shoujo manga. Classic shoujo has a hard time being exported, especially in the Anglophone sphere, and in pop culture discussions it’s generally been reduced to a subpar category of comics when compared to the high-praise shounen manga are known to receive. However, her value as a multifaceted artist and storyteller should be valued as much as other prominent authors from the ‘70s and ‘80s.

Born in 1950 in the city of Tokushima and raised on the southern island of Shikoku, detached from the glossy and busy heart of the country, Takemiya had dreamt of becoming a mangaka since her high school days. She grew up reading shounen manga and idolizing names such as Tezuka Osamu and Ishinomori Shotaro.

Such a dream was (partially) fulfilled (or at least, barely begun) in 1967, after winning first place in Mushi Production’s monthly magazine COM with her work “Kokonotsu no yūjo” (“The Ninth Friendship”). She debuted a year later in the shoujo manga magazine Margaret with “Ringo no tsumi” (“The Apple’s Sin”) at the age of eighteen.

Her budding style was heavily influenced by the aforementioned Tezuka, Naito Rune and Takahashi Macoto, three big names that helped shape the “shoujo aesthetic” we know today. She would fuse the big, rounded eyes, soft shapes, and childlike features typical of girls’ comics of the time, with exaggerated facial expressions: Takemiya’s predilection for funny faces and comedic spurs differentiated her from other female artists of the time, suggesting a more shounen-oriented approach to art.

Moving to Tokyo two years later after dropping out of University, 20-year-old Takemiya had a troublesome beginning in her career as a mangaka: stubborn and at odds with her editors, constantly late on deadlines, unsure of her work and feeling unfit for the tight constrictions the shoujo manga industry forced her into (constrictions upheld by male editors, an overwhelming majority even among artists). According to her 2016 autobiography, Shōnen no na wa Giruberu (That Boy’s Name is Gilbert), she felt like she was being forcefully attached to the shoujo label, and was even queasy at the idea of drawing girls!

Through all her insecurities, Takemiya managed to draw and write short story after short story, even though, as she recounts her feelings in her book, she was distraught with all of them. For years, she kept drawing in a sort of slump, what we could call “art block” nowadays— comparing herself with another artist with whom she was sharing a house and admired probably too much for her own good, Hagio Moto, author of works such as The Heart of Thomas (Touma no shinzou) and Marginal.

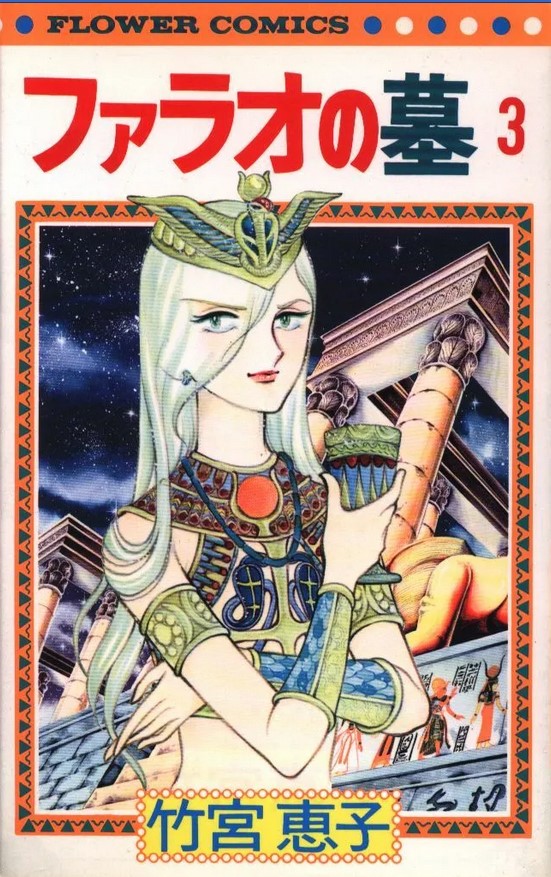

By 1974, she managed to rise to fame thanks to her first long-form story, Pharaoh no haka (The Pharaoh’s Tomb). It focuses on the tragic story of a young Egyptian prince, pushed away from his country and separated from his beloved sister, who fights to conquer his rightful place on the throne.

By the end of its run, Takemiya was steadily in the top five of shoujo magazine Sho-Comi’s popularity ratings. However, Takemiya had something very different in mind; something so different that would launch her career and place her in the big names of shoujo for years to come–as she stated in an interview with Morigawa George for the Japan Cartoonists Association in 2023.

Finally, after being successful with Pharaoh no haka, her new work focusing on the love story between the traumatized, flirtatious blond Gilbert and gentle, reserved dark-haired Serge, set in an all-male school in Provence, France, would be one of those steps that would revolutionize the manga industry: Kaze to ki no uta (The Poem of Wind and Trees). Takemiya had already written and drawn some drafts for the manga in 1971 after brainstorming with her consultant and friend, notable musician Masuyama Norie, who pushed for a new wave of more daring stories.

Both women were drawn to the figure of the “ethereal beautiful boy” (in which “boy” could also be seen as a rather androgynous character, later canonized into the term bishounen), taking inspiration from Herman Hesse’s Narcissus and Goldmund. They took a special interest in the tragic story told in the 1971 movie adaption of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice; its main actor, Björn Andrésen, inspired the design of Gilbert. Though, it seemed like the market wasn’t yet ready for such a work to be seen in a magazine for girls, leaving the project hanging for several years.

When she finally managed to publish the daringly disruptive story in 1976, Takemiya made sure to place the first explicit depiction (for the time) of an erotic scene between two boys right on the first few pages, thus letting the reader immediately understand how the drama unfolding before their eyes wasn’t like any other that had come before; a frankness that, alongside the manga’s tackling of child abuse, incest, and grooming, have notoriously helped keep it from English translation despite its legendary, influential status. These international distribution woes would likewise befall the OVA created in 1987, Kaze to ki no uta SANCTUS -Sei naru kana-, despite having the name power of one of the Mobile Suit Gundam creators–Yasuhiko Yoshikazu–as its director.

Though Kaze to ki came to pass as a staple of girls’ comics of the ‘70s and the birthplace of the current Boys’ Love genre, it wasn’t the first story focusing on queer romance Takemiya had written. “Sanrumu ni te” (“In the Sunroom”), also known as “Yuki to hoshi to tenshi to…”, (“Snow, stars, angels and…”), was a one-shot she was allowed to publish a couple of years prior to Kaze to Ki thanks to the ambiguous look of the main character, which was such that her editor was noted to mention in Shounen no na wa Giruberu that “a distracted eye could mistake him [the character] for a girl.”

The story depicted the first kiss between boys in manga history: something many fans, debuting mangaka, and Takemiya’s coworkers, were pushing to see on the pages of girl comics. It wasn’t just the need to break out of the typical heterosexual love story, but a need to create a space in girls’ comics that could tackle more serious, sometimes cruel or violent topics, such as child/sexual abuse and ethnic or class discrimination.

As Satō Masaki wrote in his 1996 essay “Shoujo manga to homofobia,” though not linking herself to political activism, Takemiya followed Masuyama’s philosophy of elevating shoujo narratives, and took her blank pages to develop stories that challenged the gender status quo, helping girls to free themselves from the sexual restrictions imposed on women.

Kaze to ki and “Sunroom” are intrinsically linked to one another but remain distinctly different. The readers would find the character of Serge Battour counters both beautiful and mysterious blonds (Gilbert in Kaze to ki, Etoile in “Sunroom”), two beauties placed on opposite sides of Takemiya’s bishounen aesthetic. If Gilbert is flirty, cocky, brash and titillating to the eye, Etoile is gentle yet detached, proper and, in a way, timid.

The stories both end in tragedy, much like the narrative fashion dictated at the time: Gilbert falls victim to drug addiction and dies in a violent accident under a carriage; Etoile, turned down by his love (also named Serge), pulls the other in for a hug and, in the process, makes the brunette stab him with a previously seen knife, dying dramatically in Serge’s arms.

The art style is also distinctly different, as the characters of “Sunroom” still retain the round and child-like features seen in most shoujo manga from the ‘60s; the paneling, meanwhile, is very static, reminiscent of Fujio Fujiko or Nagai Gou, except for some double spreads that serve as a dream-like connection between the actual scene and an oneiric world.

In Kaze to ki, on the other hand, there is an extensive amount of detail in both clothes and environments, since Takemiya had indeed visited various European countries to push for realism in her work. The design of the pages fits the ethereal, otherworldly imagery that was getting popular during the decade: huge, luscious double spreads; full body drawings cast upon the centre of the scene as other panels and balloons adorn it; shiny, big eyes, and an ever-evolving sense of growing dramatic tension as Takemiya’s story and skills unravel before the eyes of the readers.

Such love for tragedy, especially related to queer topics and relationships, was merely a projection of Japanese everyday life during the 1970s. As the economy boomed, the country kept a growing momentum, both nationally and internationally, while the general mood for the future seemed positive and hopeful.

Hence, young people craved escapism: a way of running away from their simple, everyday life became almost imperative. Thus, women and girls read how these distant, “exotic” looking boys and girls were falling in an impossible love, dooming them to tragic and melodramatic deaths.

However, among these beautiful, tragic French boys, another manga rose to fame in the shounen demographic: Toward the Terra (Tera e…). Takemiya had been offered to work on the magazine Gekkan manga shōnen with a more action-oriented title, so Toward the Terra saw the light in tandem with Kaze to ki.

Taking heavy inspiration from Alfred E. Van Vogt’s novels, Takemiya crafted a science-fiction world set in the aftermath of planet Earth succumbing to overconsumption and resource abuse. Humans, forced to flee into space, moved to other planets, colonies, and even other galaxies. In this scenario, an oligarchy comprised of men and supercomputers (the Superior Domination System, a nice and wholesome name!) controls every facet of people’s lives, starting with their births. Humans are not allowed to mate and have children as they please; instead, all babies are artificially made in external wombs and handed to “fitting” heterosexual couples.

As the generations progress, some children start developing a variety of powers such as telekinesis, telepathy, or clairvoyance because of a mutation in human DNA: their bodies, however, seem to counterbalance their newfound mental prowess with shaky health or congenital abnormalities. Treated as dangerous monsters or subhumans, they are given the name “Mu.”

Shaken by the development of such “abominations,” the central government pushes all children to undergo a mind-breaking “exam” after reaching the age of 14. All of their childhood memories get wiped and if they fail, they will be recognized as a Mu and terminated. Our protagonist, Jomy, is discovered to be a Mu (much to his surprise) and escapes death thanks to a destined encounter with Soldier Blue, the leader of the biggest if not only Mu colony, whose only goal is to find their mother planet: Terra, Earth.

The space opera’s storytelling spans generations, showing the resilience of the Mu, who still profess peace and only resort to violence when threatened by the aggression of the “human” military. It became so popular that Takemiya was granted the 25th Shogakukan Manga Award in 1980; the same year, Toward the Terra was adapted into a movie by Toei Animation. Takemiya was not keen on accepting the prize unless her other major work, Kaze to ki, won alongside her sci-fi space opera; thus, she was granted a double piece on the podium.

Although the early ‘80s movie tried to condense the story, a 2006 anime adaptation was given 24 episodes to let the five-volume story breathe. It was also given a different art style by Yūki Nobuteru (character designer for Escaflowne, Noein, and Kids on The Slope), which gave the series a makeover more suitable to the shoujo aesthetics Takemiya wasn’t allowed to include in the manga, as she states in a 2007 Rakuten interview with Hatano Eri. It also updated the storyline, pace, and character depths to be more in line with contemporary sentiments. The fresh look pushed the work back into the limelight, finding its place next to seminal sci-fi works such as the Gundam franchise by Tomino Yoshiyuki or Space Battleship Yamato by Matsumoto Leiji.

The difference with these titles is the additional queer under and overtones the story develops, especially in the more recent anime version, greatly enjoyed by Takemiya herself (we even have a Serge cameo!). The 2007 adaptation is allowed to lean much further into sexual ambiguity with characters such as Keith (the anti-hero), especially towards Jomy, Keith’s school friend, Sam, or his underling, Matsuka. It’s probably the best way to experience the story, filling in the gaps that young age and constricted deadlines didn’t allow for in the late ‘70s, and pushing some changes that, overall, only expand and perfect the heartfelt narrative.

Toward the Terra is a perfect example of the overt political views Takemiya holds, critical of a fascist government that structurally hinders humans from evolving past “set societal norms”: childhood is forcibly erased; parenthood is only allowed in normative, heterosexual relationships; and any “active” agent of social change or any deviation from that norm must be eliminated.

The critical view of society Takemiya presents in her works still holds its ground in the scope of current Japan (and, well, in general), making “Toward the Terra” a classic that can be revisited and re-read, offering different interpretations each time. Much like other stories from those years, we don’t see a happy ending, though hope remains at the end for a new future, a different future!

Takemiya continued to create manga until 2000 when she was offered a teaching position at Kyoto Seika University. However, she remained active in the field of teaching the craft of being a comic artist through essays and books. As a teacher and, later, the university president (from 2014 to 2018), she was able to pass the torch to budding artists not unlike herself fifty years ago.

While she has never received the same level of formal acclaim as her contemporary Hagio Moto, Takemiya Keiko’s works can be arguably considered foundational for what we consider women’s literature, or literature in general, from the last century. Thanks to her push towards more complex and daring topics, she managed to expand the horizon of manga for girls, without sacrificing the feminine qualities of her artistic and narrative style.

As is often seen, both online and off, art made for and by girls and women tends to suffer under the pressure of mass-media consumption, which usually focuses on a presumed male reader; enjoying a piece by Takemiya, much like many other female artists from the ‘70s (such as Yamagishi Ryouko or Ikeda Riyoko), shows its shoujo roots with pride, assuring both depth and quality because they are works for a female audience and not in spite of.

In the posthumous 1991 essay “On reading classics” (Perché leggere i classici), famous Italian writer Italo Calvino explained what we can consider a “classic”: a work that keeps on teaching us even after multiple readings, even after years and years from its first inception. Takemiya’s manga will persist with the same spirit.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.