Content Warning: Discussion of transphobia

Around the start of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, Chiaki Hirai published an article about Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou, comparing the post-apocalyptic manga to the threat posed to humanity by the novel coronavirus. It was a perspective piece—and a rumination—on societal collapse as it was happening around the author, when so little was still known about the nature of the virus, and what the extent of its impact on us was going to be. Now, at the start of 2023, our world has been forever changed. While the virus continues to mutate into new strains, governments have largely chosen to ignore the ongoing effects of the pandemic in exchange for a “return to normal,” moving on with or without us. Post-apocalyptic fiction has felt closer to home, especially for marginalized readers.

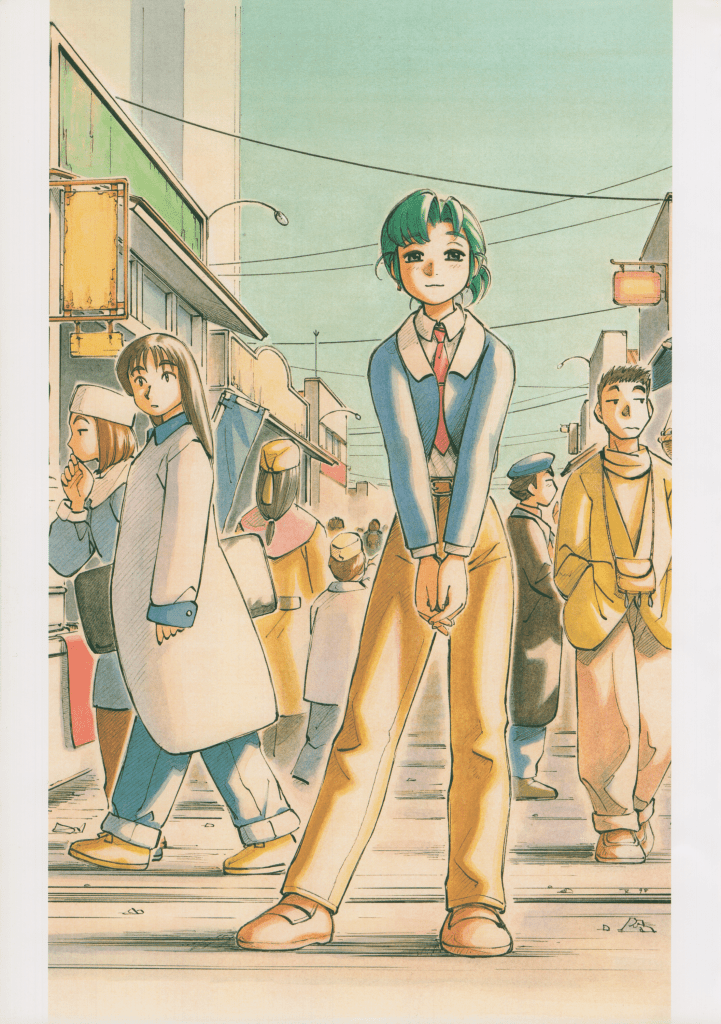

Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou (hereafter YKK) focuses on Alpha Hatsuseno, an android girl entrusted with a café by an owner who abandoned it, and her, without clear reason, leaving her to run it in a mostly uninhabited post-apocalyptic world. While most stories that imagine a post-apocalyptic setting depict a world in ashes, strewn with death and danger, YKK’s world is mostly one of peace and solitude for those survivors who remain. Cities lie silent beneath a solemn ocean; wind sifts through the stalks of amaranth sprouting from old, cracked roads. Overlooking land, sea, and sky is Café Alpha, a humble building on a hill and a relic from before “The Age of Evening Calm”—otherwise known as the end of the old world. And, for us, 2020 was our own Age of Evening Calm, as Hirai described;

“Dark grey clouds wafted overhead, but the air was fairly clear and San Francisco’s cityscape gleamed in the distance. There was hardly a car around me, even though I was driving at 8 a.m. What would normally be a packed freeway with bumper-to-bumper traffic, I sped through without pause on my way across the Bay Bridge. There is beauty in desolation.”

The story of Alpha Hatsuseno, an android girl in a collapsed world, serves as an allegory for what many transgender people went through during the pandemic. In the solitude and desolation of COVID-19, cut off from the pressures and expectations of society, there was a silent wave of transgender people coming to the realization that they no longer needed to pretend to be someone they were not, beginning their transitions in the midst of death, despair, and loneliness. Sølvi Goard described the connection between androids—or “cyborgs”—and transgender people in a 2017 article about transfeminism through an anecdote about the film Ghost in the Shell:

“[The] questions – Am I really real? Have I ever existed? Or am I a ghost of an identity? – are ones many trans people will recognise: the visceral confusion that comes about from knowing how you feel and experience your body, but having that experience jar so powerfully with what meaning other people and society give to it. It is a question that Ghost In The Shell’s non-cyborgs never really have to ask: as long as cyborgs exist then a certainty in their humanity is assured. In the same way, cis society rarely has to justify its claims to gender normality. Maybe it would be useful if it did.”

Today, in our post-apocalypse daily lives, the highways are packed again. Cafés are full, students attend their classes and extracurriculars, libraries have seen a comeback, and gays attend Taylor Swift parties at local venues and sing their hearts out. These are some of the pleasures of surviving the apocalypse. A return to society has meant, for many, a return to being human. Yet at the same time, we have seen a rise in some of the most inhumane state-sanctioned transphobia and homophobia to occur in decades. Uganda’s anti-gay death penalty bill, the United States’ erosion of transgender rights in conservative states, and the continued assault on transgender people’s rights in British society are signs that in some cases, for trans people, the apocalypse never ended. Like the coronavirus itself, it has only continued to evolve. For trans people, the return to society has been complicated by the fact that many of us are different people than who we were when the pandemic first hit. Within what felt like a silent, depopulated world, many of us found ourselves asking who we really were when most of the societal expectations that shaped our identities and roles no longer applied.

Alpha’s apocalyptic world is also one of pure self-discovery. There is no society to place demands and expectations on her. No social compact, no tax, and no institutions creating barriers between her and her access to a full life. While Alpha had likely been designed and created to perform menial labour such as working in a café, in the absence of that labour she has become increasingly human and less of a machine. She remarks early in the narrative that although her “lachrymal glands” were designed for no reason other than to maintain the health of her “optical tissues,” she has twice been moved to tears by emotion alone. Once, when she is playing music to herself on a lute, and again when her friend and nearest neighbour, Ojisan (or “Uncle”), takes her to the hospital where she receives a skin replacement after being struck by lightning. Waking up at the hospital, she thinks to herself:

“I started crying for some reason. My tear ducts are just supposed to moisten my eyes, and yet… It’s happened to me a few times while playing the moon guitar by myself. This feels different than that. But I like the feeling.”

For all that she was designed to be a machine whose very tears are of purely mechanical utility, her humanity, like a teardrop, escapes. Like any person, the trauma of being hospitalised after a freak accident has shocked her, while the love she feels from Ojisan, his grandson Takahiro, and Alpha’s surgeon has confronted her with the reality of her emotions and how they transcend what she was intended to be. Surrounded by her chosen family who love and support her (even the surgeon remarks that she sees Alpha “like her own daughter”), Alpha is not only allowed to embrace that she is human, but show it externally and live it.

The more others get to know Alpha, the more difficult it becomes to see her as anything but human. There is an evening, not long before the lightning-strike accident, when Uncle and Takahiro visit her at her café and she plays her moon guitar for them. Playing the moon guitar, or lute, was something she used to do for her owner before he left, who had presumably trained her for the task. But after his departure, playing the instrument became something she did for herself and her own enjoyment. Ojisan is so captivated by her performance that as he watches the way her guitar-playing and humming come together, he thinks to himself: “Times like this, I wonder if Alpha-san could really be a robot. She seems so darn human.”

When we view Alpha as an analogue for a trans woman, this moment evokes the way gender is perceived in our world, and how trans people’s humanity is contingent upon that perception. Her emotive and personal performance of music causes her to “pass” as a “biological human” to Ojisan, to the point where he doubts whether she is really an android at all.

Similarly, performance of gender in our world is often a necessity for us as transgender people to have our humanity witnessed and acknowledged by cis people, even when that performance may not be authentic to who we are as individuals. A trans woman might find herself under pressure to adhere to the most rigid of gendered expectations for women, training her voice to be higher than even the average cis woman’s voice and wearing stereotypical, sometimes outdated feminine fashion, in order to “pass” as cisgender women. Meanwhile, all we want is to be seen and acknowledged the way Ojisan sees Alpha: human despite her physical packaging in a cyborg body. Ojisan, who has seen Alpha at her most vulnerable, after the lightning-strike, having spoken to the surgeon about the specificities of operating on androids, sees past those trivialities into her soul itself. That soul, which she reveals on her own terms in her musicality and emotivity, is undeniably human.

Her sentimentality towards memory is another facet of her growing humanity. One day, a package is delivered to her by another android girl, Kokone, which contains a camera from the previous owner of the café. When discovering that Kokone is also an android, albeit a newer model, Alpha is in disbelief, having not “clocked” Kokone as being like her. It is then Kokone’s turn to be surprised that Alpha herself can’t identify an android, saying “Anyone can tell! From their ambience, or the green or purple hair…” Alpha had been unaware that there were such obvious physical signs of android-ness and the exchange shakes her.

The scene is the equivalent of two trans women meeting, and in the absence of cis people, their reality as women is not dependent on “passing” as cis. Instead, they are women just because they are, even if there are signs that point to a different physical provenance. Kokone relays a message to Alpha through a kiss, a rather sapphic form of data transfer that Alpha clearly, though bashfully, enjoys. In the message, the owner tells her to use the camera to record pictures of anything she likes that she would want to reflect upon later in life. Her indecision about what to take a picture of, about what to use her limited three hundred shots on, shows her sensitivity towards memory-making. She senses an innate responsibility to the future.

All around her are remnants of the old, human world that has died. Alpha, like the buildings, street lamps, vehicles, and sunken cities, was a creation of that generation of humans, but is imbued with the capacity to feel and think as a “true” human being would. And she bears the responsibility of preservation: not of the past, but of the collapsed present. In Alpha’s camera, and in her tears, which she sheds at the sight of that forgotten world, there is a reckoning with the enormity of loss as well as the beauty present in the desolation she lives in. There is also the implication of a hope that humanity will recover from this calamity gradually, giving purpose to her photographic recording of what their post-apocalyptic world was like.

Like many transgender people, Alpha Hatsuseno may not have been seen as fully human by society prior to its collapse. The physical differences that set her apart from biological humans may have led some to view androids as less than human: things that assumed a human form, but in their essence are anomalies. People may even think of them as freaks, unable to feel, think, and live familiar experiences. But in the time after society’s collapse, Alpha is able to assume her full humanity. What is the purpose of a servant robot once the society she was built to serve no longer exists?

For Alpha, the apocalypse offered a world that no longer divided humanity between “organic” and “machine.” In that context, she became able to chart a new path for humanity, simply by being an android whose purpose is to record human history from her perspective. But is it human history if the historian is not considered a person? Science fiction lets us test the boundaries of what is considered “natural” and “normal,” enabling its readers to imagine new futures. The Age of Evening Calm in Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou allows Alpha to break down the barriers between human and android and create her own sense of destiny and meaning. Likewise, trans people’s very existence begs the invention of a new humanity in which transness is natural from the start. Within a cisgender society, an apocalypse usually means the end of the world. Yet for trans people, it can be a new beginning.

Comments are open! Please read our comments policy before joining the conversation and contact us if you have any problems.